Boys Go to Baghdad, Real Men Go to Tehran

Has the moment Iran was always meant to face finally arrived?

Boys Go to Baghdad, Real Men Go to Tehran was not a joke, nor a fringe provocation. It was a slogan that circulated openly in neoconservative policy circles in the early 2000s, capturing a worldview in which the 2003 invasion of Iraq was never the final objective, but merely the opening act. Baghdad was framed as the easy target; Tehran was always the real prize. Iraq, in this logic, was the warm-up. Iran was the test of seriousness.

The phrase reflected a broader post-9/11 ambition: to reorder the Middle East through force, dismantle hostile regimes, and eliminate what was later labelled the “Axis of Evil.” Afghanistan fell first, then Iraq. Libya and Syria followed through different forms of intervention. Iran, however, remained unfinished business—too complex, too costly, too dangerous to confront directly, yet never removed from the strategic imagination.

Two decades later, the slogan has resurfaced—not as rhetoric, but as a question. Iran is under unprecedented internal pressure, its regional network has been severely weakened, and its deterrence exposed in ways few anticipated. U.S. military posture has hardened, Israel has escalated, and the language of confrontation has returned to the centre of policy debates in Washington. What once sounded like bravado now appears, to some, like delayed inevitability.

The question, then, is no longer whether Iran was always meant to be confronted, but whether the conditions imagined by those early slogans have finally materialised?

The Neocon Vision: The War Against the “Axis of Evil”

The attacks of 11 September 2001 did more than trigger a global security response; they produced a new strategic worldview in Washington. Under the banner of the “War on Terror,” a group of neoconservative policymakers advanced a far more ambitious project: the remaking of the Middle East through force. Terrorism, in this framework, was not merely a security threat but a symptom of hostile regimes that needed to be removed and replaced.

This vision quickly took institutional form. In his 2002 State of the Union address, President George W. Bush publicly identified an “Axis of Evil,” placing Iran alongside Iraq and North Korea as core threats to U.S. security. But behind the public rhetoric was a broader, less formal list of states viewed as obstacles to a new regional order. Afghanistan was first, toppled within weeks of the 9/11 attacks. Iraq followed in 2003. Libya was later dismantled through NATO intervention. Syria was targeted through sustained pressure, proxy warfare, and sanctions aimed at regime collapse.

Iran stood apart. It was always on the list, but it was also the most difficult case: larger, more cohesive, militarily capable, and deeply embedded in the region through ideological and proxy networks. Unlike Iraq or Libya, Iran could not be isolated or overwhelmed without risking a regional war. As a result, while other targets were confronted directly or indirectly, Iran was deferred.

This deferral should not be mistaken for abandonment. In neocon thinking, Iran was never forgotten—only postponed. The assumption was that once easier regimes fell and the region was reshaped, Tehran would either collapse under pressure or face confrontation from a position of American strength. The slogan “Boys Go to Baghdad, Real Men Go to Tehran” captured this hierarchy clearly. Iraq was a step; Iran was the destination.

What history would later reveal is that postponement was not neutral. Each intervention reshaped the region in ways that strengthened Iran’s influence rather than weakening it. Yet the original ambition never disappeared. It lingered beneath policy debates, waiting for a moment when conditions might once again make Tehran appear vulnerable—and confrontation seem feasible.

Why Iraq Was the Easy Target

By the time U.S. forces crossed into Iraq in March 2003, the country had already endured more than a decade of systematic weakening. The invasion did not strike a functioning state at the height of its power; it hit a society and political system that had been steadily dismantled since the 1991 Gulf War.

That war marked a decisive rupture. Iraq’s military—once one of the largest in the region—was crushed in weeks. Critical infrastructure was destroyed, including power grids, water treatment facilities, transportation networks, and industrial capacity. Although the regime survived militarily, the foundations of the state did not. Iraq emerged from the war severely degraded, dependent on emergency repairs and international relief.

The sanctions regime that followed compounded the damage. Throughout the 1990s, comprehensive economic sanctions collapsed Iraq’s economy and hollowed out its institutions. State salaries became symbolic, public services disintegrated, and governance shifted from bureaucratic administration to informal survival networks. Crucially, sanctions did not merely punish the regime; they dismantled the state’s capacity to function.

The social consequences were equally profound. Large segments of Iraq’s technocratic and professional classes emigrated, taking with them administrative expertise, institutional memory, and technical skill. The middle class—historically the backbone of state capacity and social stability—was eroded. What remained was a society fractured by poverty, dependency, and fear, with institutions unable to absorb shock or manage transition.

As a result, Iraq entered 2003 already weakened, isolated, and fragmented. The regime collapsed quickly once confronted with overwhelming force, but there was no resilient state beneath it. This distinction proved decisive. Removing Saddam Hussein did not simply remove a ruler; it removed the last remaining structure holding the country together.

The lesson was stark: regime collapse does not equal state survival. Iraq fell easily not because regime change is inherently simple, but because the state itself had already been dismantled. This is precisely what made Iraq an “easy” target—and precisely why the same logic cannot be mechanically applied to Iran, at least at this stage.

Winning the War, Losing the Peace

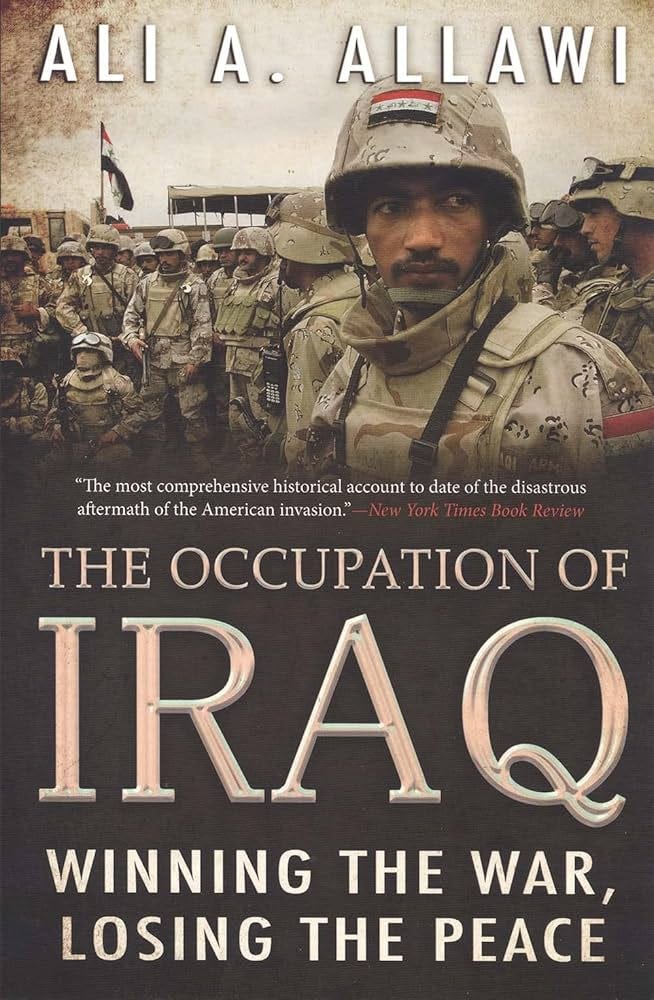

Iraqi scholar and former finance minister Ali A. Allawi captured the core failure of the 2003 invasion with a phrase that has since become diagnostic: winning the war, losing the peace. The United States achieved a swift and overwhelming military victory, but it entered the post-war phase without a coherent political strategy for what would follow. What unfolded was not reconstruction, but unraveling.

The invasion was planned almost exclusively as a military operation. There was no serious, unified plan for post-war governance, no agreed vision for state reconstruction, and no institutional continuity strategy. The dismantling of Iraq’s army and bureaucracy removed what little remained of state capacity, while no viable political alternative was prepared to replace it. Power vacuums were filled not by democratic institutions, but by militias, sectarian actors, and external patrons.

The method of intervention deepened the problem. A full-scale ground invasion placed tens of thousands of U.S. troops inside a complex social and political landscape they neither controlled nor fully understood. This made American forces highly vulnerable to insurgency, asymmetrical warfare, and local resistance. The longer the occupation lasted, the more legitimacy eroded—both for the occupiers and for any political order associated with them.

Regionally, the invasion triggered widespread rejection. Neighbouring states did not see Iraq’s transformation as stabilising or legitimate; they viewed it as a threat or an opportunity. Some became active spoilers, fueling insurgency, supporting proxies, or exploiting the chaos for their own strategic gain. Instead of reshaping the region in Washington’s image, the war destabilised it.

The lesson of Iraq is not that military force is ineffective, but that force without political architecture is destructive. Winning battles does not produce order; it merely removes obstacles. Without a credible post-conflict framework, military victory creates conditions for chaos rather than control. This failure would later loom large over every discussion of Iran—serving as both a warning and a constraint on those tempted to believe that Tehran could be handled the same way Baghdad was.

Iran Contained, Not Confronted: The Boiling Frog Strategy

After the experience of Iraq, direct invasion lost its appeal as a tool for dealing with Iran. The costs were too high, the risks too unpredictable, and the political fallout too severe. Instead, U.S. strategy shifted toward a slower, more indirect approach: containment through overextension. Iran would not be confronted head-on; it would be allowed—and in some cases encouraged—to stretch itself thin.

This strategy rested on a calculated assumption. By permitting Iran to expand its regional footprint, build proxy networks, and insert itself into conflicts across Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen, Tehran would gradually exhaust its resources and legitimacy. Influence would come at a price: financial strain, growing enemies, and deepening exposure. Regional expansion, once framed as strategic depth, would become strategic liability.

Sanctions became the central lever of this approach. Under the banner of “maximum pressure,” economic restrictions were designed to serve two interconnected goals. Externally, they aimed to weaken Iran’s ability to sustain regional allies and military capabilities. Internally, they were intended to generate social and economic pressure that would translate into political unrest. U.S. Treasury officials openly framed sanctions as a mechanism that constrained the state by squeezing society—an approach that, by their own assessment, contributed to protests and the erosion of domestic legitimacy.

Over time, the effects compounded. Iran became increasingly overextended abroad, forced to defend a wide arc of influence with diminishing resources. At home, economic hardship deepened grievances, exposing cracks between state and society. Regionally, Iran found itself surrounded not by allies, but by wary neighbours—many openly hostile, others quietly distancing themselves, choosing silence over confrontation.

This was the logic of the boiling frog. Iran was not pushed into immediate crisis; it was allowed to adapt, expand, and commit—until the accumulated weight of commitments, sanctions, and isolation left it vulnerable. Containment did not seek collapse in one decisive blow. It aimed instead at gradual weakening, setting conditions where Iran would face pressure from all directions at once, with fewer options and fewer friends.

The 7 October Moment: From Containment to Exposure

The attacks carried out by Hamas on 7 October marked a decisive rupture in the regional balance. More than a shock event, they became a strategic opening—one that rapidly shifted the logic of dealing with Iran from indirect containment to direct exposure. What followed was not an isolated military response, but a broader effort to dismantle Iran’s regional network under the cover of crisis.

The scale and brutality of the attack provided political justification for actions that had long been debated but rarely executed at full force. Iran’s proxies, once treated as manageable irritants within a contained framework, were reframed as existential threats requiring systematic degradation. The response unfolded across multiple theatres, targeting command structures, logistics, leadership, and operational depth. What had previously been tolerated as part of a proxy equilibrium was now treated as an integrated adversarial system to be broken.

Regional dynamics amplified this shift. Across much of the Arab world, dissatisfaction with Iran’s regional role had been building for years. Tehran’s strategy—whether intentionally or as a by-product of its security calculations—was structured in ways that contributed to the destabilisation of neighbouring states and the entrenchment of sectarian politics. Even where this outcome may not have been Iran’s original intent, the cumulative effect eroded sympathy among governments that had traditionally been cautious about direct confrontation. As the escalation unfolded, many regional states either quietly supported efforts to weaken Iran’s network or chose strategic silence—an absence of resistance that proved as consequential as overt backing.

The escalation culminated in what became known as the twelve-day war, a turning point that brought conflict closer to Iran’s own territory in ways previously unthinkable. Air defence systems were penetrated. Senior military commanders were eliminated. Sensitive and strategically significant military and industrial sites were struck. For the first time in decades, Iran’s internal security architecture appeared exposed rather than insulated.

The implications were profound. Iran was no longer the fortified stronghold many had assumed—capable of projecting power outward while remaining immune at home. The events shattered long-standing threat assessments that portrayed Iran as resilient, impenetrable, and strategically untouchable. Containment had given way to exposure, and with it came a recalibration of how Iran’s strength, deterrence, and vulnerabilities were understood.

Will Trump “Go to Tehran”?

If the neoconservative era was defined by regime change through occupation, Trump’s approach represents a clear departure. His central lesson from Iraq is not moral but strategic: boots on the ground create vulnerability, drain legitimacy, and entangle the United States in conflicts it cannot control. Occupation is off the table. So is nation-building.

Instead, Trump’s preferred model relies on short, fast, coercive action—combining military pressure with psychological warfare. The objective is not conquest, but submission: to shock, disorient, and force compliance without triggering a prolonged war. Airpower, standoff strikes, cyber operations, sanctions, and constant signalling are used to compress decision-making time in Tehran and raise the cost of resistance.

The terms Trump seeks are explicit and maximalist. Iran would be required to abandon any nuclear program entirely, accept severe and verifiable limitations on its missile capabilities, and end all support for resistance movements across the region. In effect, Iran would be asked to surrender the pillars of its deterrence and ideological reach without the regime itself being formally removed.

This leaves Tehran facing a stark dilemma. Acceptance would not stabilise the regime; it would initiate a slow erosion of its foundations. Stripped of its strategic tools and regional identity, the state would lose both its external leverage and much of its internal ideological base. Resistance, however, carries the risk of massive destruction—military, economic, and institutional—at a scale that could permanently cripple the country.

The decisive variable is Iran’s capacity to retaliate. If Tehran can impose costs high enough to credibly threaten a wider war—drawing in U.S. forces, destabilising allies, or disrupting global markets—Trump is likely to pull back. In that scenario, a new deterrence balance would emerge, and terms would inevitably shift in Iran’s favour. If Iran cannot do so, the alternative is prolonged coercion: keeping the country weakened, sanctioned, and strategically broken, waiting for a future moment of collapse—much as Iraq was contained after 1991 and finally shattered in 2003.

Whether Trump ultimately “goes to Tehran” depends less on intent than on calculation. The question is not whether force will be used, but whether Iran can make the cost of using it intolerably high.

An interesting concluding prospect:

"Whether Trump ultimately 'goes to Tehran' depends less on intent than on calculation. The question is not whether force will be used, but whether Iran can make the cost of using it intolerably high."

This state of affairs is like an asymmetrical, unstable and unpredictable version of Cold War nuclear deterrence.

On the one side Iran would seem to have achieved the capacity to deter American regime change despite lacking the nuclear means of deterrence. This is an inherently unstable situation, since President Trump’s particular antagonism to Iran's nuclear program, and America's broader geostrategic commitment to Israel’s strength in the region will continue to motivate American pressure on Iran but, short of decisive military intervention, American threats will surely continue to be met by Iranian counter threats.

Since American nuclear capacity provides a superiority over Iran that prevents the anxious stability of the Cold War's Mutually Assured Destruction, such an atmosphere of threats and counter-threats does not encourage restraint on America's part.

The longer the presently heightened atmosphere lasts, the higher the danger. Real asymmetry of power and rhetorical sabre-rattling produce ambiguities of intention and perception, while American toughness and resolve may fall prey to the American crusade impulse. Ongoing instability also increases the risk of either side resorting to premature aggression, not to mention making errors of judgement under strain.

On the American side, President Trump’s attitude to Iran is perfectly consistent with what Daniel Benjamin and Steven Simon have called America's 40-year obsession with its Iranian "great Satan." But since the dynamics of intention and calculation in Trump’s foreign policy are rather obscure , the traditional American animus toward Iran has already been expressed in drastic projections of American power under Trump - the bombing of Iranian nuclear sites last year being the most aggressive (but not obviously the most successful) example.

If forewarning Trump that the cost of "going to Tehran" will be intolerably high results in Trump recognizing the danger of catalysing massive regional turbulence, a prudent president would of course pull back.

But it's not the easiest thing to imagine the current American president accepting that temperance has been forced upon him by the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic. Even harder to imagine that relenting temporarily would lead Trump to develop an interest in a policy of ongoing strategic restraint.