Between Collapse and Reform: Iran’s Real Democratic Path

In an age seduced by easy solutions (collapse), the hard work of negotiation—not revolution or intervention—is how democracies are actually built.

In moments of deep frustration and repression, the appeal of foreign intervention grows louder. When images of violence circulate and political space narrows, the promise of an external saviour can feel not only justified, but urgent. For many, it appears to offer clarity: decisive action, rapid change, an end to stagnation. The language becomes simple—strike, intervene, remove, replace. In such moments, complexity feels like complicity, and patience feels like betrayal.

The emotional logic is powerful. If the system is closed, break it. If reform seems impossible, collapse it. If negotiation fails, force the outcome. Quick solutions are seductive precisely because they bypass the slow, uncertain, and often humiliating work of political bargaining. They offer catharsis where politics offers compromise.

But beneath the anger lies a more serious question—one that cannot be answered emotionally. Do we want justice in its most immediate and retributive sense, or do we want survival as a functioning society? The two are not always the same. History suggests that when collapse is chosen as a shortcut to justice, survival often becomes the first casualty.

Revolutions Devour States, Not Just Regimes

Revolutions are often imagined as surgical acts: the tyrant falls, the system resets, the people rise. But history tells a different story. Revolutions rarely remove power structures cleanly. They dismantle institutions, fragment authority, and create vacuums in which the most organised and disciplined actors—usually armed and ideologically rigid—prevail.

The first dynamic is ideological purification. Revolutions are powered by moral clarity, but once in motion, that clarity becomes exclusionary. Moderates are accused of betrayal. Pragmatists are labelled corrupt. Purges follow—not only of the old regime’s loyalists, but of fellow revolutionaries who fail the test of “purity.” What begins as liberation becomes internal cleansing. We can see plently of examples now among the opposition groups who are attacking each others even bwefore getting into power.

Second, revolutions unleash intra-elite conflict. When the old order collapses, multiple counter-elites compete to define the future. Secular versus religious, nationalist versus separationalists, armed versus civic—these factions do not peacefully negotiate authority. They fight for it. The revolution begins devouring its own children long before it consolidates power.

Third, the collapse of institutional authority produces a vacuum. Armies fracture, bureaucracies stall, courts lose legitimacy. In that space, the most organised networks—often those already structured around armed struggle—move quickly to monopolise force. A temporary “revolutionary guardianship” emerges, justified as necessary to protect the revolution from enemies. That guardianship often hardens into permanent rule.

Revolutions also destroy social architecture. They do not merely replace leaders; they dismantle the frameworks that hold society together: administrative continuity, economic systems, professional classes, civil associations. The result is not simply regime change, but state erosion.

Paradoxically, while revolutions claim to dismantle authoritarianism, they frequently generate stronger, more centralised states, if they become eventually successful in overcoming the choas. In order to defend against internal and external threats—real or perceived—the new leadership expands security powers, institutionalises emergency rule, and builds parallel enforcement bodies. The revolution that began as a rejection of domination ends by concentrating authority more intensely than before.

Finally, many revolutions experience what scholars describe as the “second revolution” phenomenon. Once power is secured, new enemies must continually be identified to preserve revolutionary legitimacy. The logic of permanent mobilisation replaces the logic of stable governance. Vigilance justifies repression; repression justifies further vigilance.

Iran’s 1979 revolution followed many of these patterns—an experience examined in more detail in my previous piece, “Arming Iranian Protesters: What Would Actually Happen?” What began as a broad-based uprising against monarchy evolved into prolonged internal conflict, the rise of parallel armed structures, and the consolidation of a securitised state. The lesson was not unique to Iran. It was structural.

Why the American Revolution Is Often Treated as an Exception

At first glance, for many, the American Revolution appears to contradict the argument that revolutions devour institutions and destabilise societies. The United States did not descend into prolonged cycles of terror or dictatorship after 1776. Instead, it produced a durable constitutional order. But this outcome is less evidence that revolutions create democracy—and more evidence that democracy had already been socially embedded before the rupture with Britain.

By the time independence was declared, much of the democratic infrastructure in the American colonies already existed at the societal level. Colonial assemblies, town halls, local councils, and forms of representative governance had functioned for decades. Property-owning male citizens were accustomed to electing local officials, debating public matters, and exercising a degree of self-rule. Political participation was not invented in 1776—it was institutionalised long before.

Crucially, the American Revolution did not dismantle the entire administrative, legal, and social infrastructure of colonial society. Courts continued to function. Property rights remained largely intact. Economic elites retained influence. The revolution replaced imperial sovereignty with domestic sovereignty—but it did not fundamentally overturn the underlying social hierarchy. Enslavement persisted. Indigenous dispossession continued. Women were excluded from political rights. The “power structure deep down” remained largely intact; what changed was the locus of ultimate authority.

The American case was different because authority did not emerge from revolutionary violence alone. It emerged from a process of negotiated foundation. Local town meetings elected representatives to state constitutional conventions. State delegates then selected representatives to draft the federal constitution. This stepwise delegation of power under mutual consent allowed citizens to experience what Arendt called “public freedom”—the act of collectively founding a political order. Authority flowed not from destruction, but from participation.

In that sense, the American Revolution did not create democracy out of collapse. It formalised and nationalised political practices that were already in place. It was less a social rupture than a sovereign transfer.

This is why the American case is often misapplied in contemporary debates. It is remembered as proof that revolution produces liberty. But its success depended on pre-existing institutions, local self-governance traditions, and gradual political development. Without those foundations, a revolutionary break would likely have produced fragmentation rather than stability.

The lesson is not that revolution can never succeed. It is that where democratic norms and institutions are already socially rooted, rupture may formalise them. Where they are not, rupture tends to destroy more than it builds.

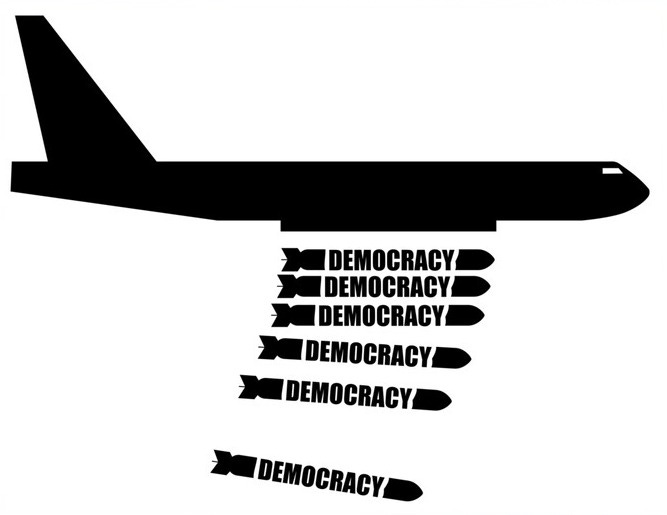

Foreign Intervention: You Cannot Bomb Your Way to Democracy

External force can remove a regime. It cannot construct political legitimacy.

Modern history offers repeated evidence of this distinction. Military intervention may achieve rapid battlefield success, but democracy is not a battlefield outcome—it is a political architecture built slowly through institutions, bargaining, and social consent.

Iraq in 2003 demonstrated the gap between regime removal and state survival. The U.S.-led invasion achieved swift military victory. Baghdad fell in weeks. Yet the dismantling of state institutions—army, bureaucracy, and security apparatus—produced institutional collapse, sectarian fragmentation, insurgency, and years of instability. It took more than fourteen years and well over a million casualties before Iraq reached even a fragile and incomplete equilibrium—and it remains structurally unstable.

Libya followed a similar trajectory. International intervention removed Muammar Gaddafi quickly. But there was no coherent post-conflict architecture. The result was militia rule, competing governments, and the erosion of sovereignty. Regime removal did not produce a unified state; it produced fragmentation.

Syria offers an even more devastating lesson. What began as largely peaceful protests became militarised, then internationalised, and ultimately transformed into a multi-layered proxy war. Fourteen years of conflict, roughly 700,000 deaths, and the destruction of much of the country’s infrastructure later, the regime was eventually weakened and reshaped—but the state itself was shattered in the process. Victory, if it can even be called that, came at the cost of national devastation.

The structural reason is simple. Democracy requires institutional continuity, political bargaining, social contracts, and a monopoly of violence under law. War systematically destroys each of these foundations. It fragments authority instead of consolidating it. It empowers armed actors rather than civic ones. It replaces negotiation with coercion.

Foreign intervention may accelerate the fall of a government. But it rarely accelerates the birth of a stable democracy. More often, it prolongs instability, multiplies casualties, and leaves societies to rebuild from ruins that did not previously exist.

Iran Is Not an Exception

A common response to these comparisons is immediate and confident: Iran is not Iraq. Iran is not Libya. Iran is not Syria. The implication is that Iran possesses some structural immunity to the fate that befell those states.

History and present realities suggest otherwise.

Iran is indeed a historically cohesive civilisation with deep bureaucratic traditions and a strong sense of national identity. But those characteristics did not prevent systemic rupture in 1979. As discussed in my previous article, “Arming Iranian Protesters: What Would Actually Happen?”, the Iranian Revolution did not produce an orderly democratic transition. It dismantled institutions, empowered the most organised armed actors, triggered internal armed conflicts in multiple regions, and consolidated a new securitised state under the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. The lesson is clear: national depth does not immunise a country from revolutionary fragmentation.

Today’s structural conditions are not fundamentally different in ways that would guarantee a better outcome under foreign intervention.

First, Iran’s security apparatus remains highly capable, centralised, and ideologically cohesive. Unlike Iraq in 2003, there are no visible fractures at the top command level that suggest imminent institutional collapse. Any sudden external shock would likely trigger intensified securitisation rather than orderly transition.

Second, opposition forces lack unified organisation inside the country. The most vocal external current—monarchist groups advocating the return of the crown—has almost no organisational infrastructure on the ground. There is no parallel chain of command, no shadow bureaucracy, and no demonstrated ability to mobilise or coordinate nationwide institutions. Crucially, there is no visible pathway for large-scale elite defection from within the state apparatus in their favour.

Third, Iran contains its own internal fault lines—ethnic, sectarian, regional, and economic. These divisions are currently managed within a centralised state structure. A sudden collapse under military pressure would not automatically produce democratic pluralism; it could just as easily produce fragmentation, armed competition, and competing power centres—particularly in border regions.

Fourth, Iran’s regional entanglements make it even more vulnerable to proxy dynamics than pre-2003 Iraq. Any external intervention would not occur in isolation; it would activate regional rivalries, intelligence networks, and non-state actors with experience in irregular warfare. The battlefield would not remain contained.

The argument that “Iran is different” often rests on emotion if not Persian-supremacy racism rather than institutional analysis. It assumes that anger will translate into cohesion, that regime collapse will automatically produce democratic order, and that foreign backing will accelerate rather than distort domestic political development.

But democratic transition is not a reward automatically triggered by regime removal. It is the product of negotiated political architecture, institutional continuity, and elite bargains that prevent total collapse. None of these conditions are strengthened by external military intervention.

Iran’s history does not show structural immunity to fragmentation. On the contrary, it shows how rapidly revolutionary rupture can produce a securitised state. The absence of a unified, internally organised, institutionally embedded alternative today makes the risks of externally induced collapse even more acute.

The real question is not whether Iran resembles Iraq, Libya, or Syria. The question is whether it has the institutional safeguards that those countries lacked when their state structures were violently disrupted. At present, there is little evidence that such safeguards exist outside the very system many seek to dismantle.

I Saw Regime Change Up Close. It Did Not Bring Democracy

I was not a defender of Saddam Hussein’s regime. I was an opponent of it. I believed it had to end. Like many Iraqis inside and outside the country, I saw 2003 as the beginning of a long-awaited liberation. When Baghdad fell, I felt hope—real hope—that democracy was finally within reach.

I returned to Iraq in mid-April 2003. I expected to witness the birth of a new political order. Instead, I witnessed the collapse of a state.

There is a critical difference between the fall of a regime and the destruction of a state. In Iraq, both happened simultaneously. The army dissolved. The police vanished. Ministries were looted. Archives burned. Courts stopped functioning. Borders became porous. Authority evaporated overnight.

What followed was not an orderly transition but a vacuum.

Into that vacuum stepped militias—some ideological, some sectarian, some criminal, some backed by foreign powers. The logic of weapons replaced the logic of institutions. Politics became militarised. Identity hardened. Suspicion deepened.

I worked in Iraq as a journalist, activist, and later as a politician. I founded civil society organisations focused on human rights and minority protection. I served as an international media editor. Years later, I became a senior adviser to the Iraqi prime minister. I witnessed the state’s destruction from multiple vantage points: on the street, in the newsroom, in civil society, and inside government itself.

The country stood on the edge of total collapse. Division was not theoretical—it was unfolding. Civil war was not speculation—it arrived. Entire communities were displaced. Sectarian killings scarred cities. Public trust disintegrated. The very idea of a shared national future fractured.

And rebuilding did not happen quickly.

It took years—long, painful, exhausting years of negotiation among rival politicians who had little trust in one another. It required reluctant cooperation from neighbouring countries that had initially fuelled competition. It required enormous international involvement. In some moments, it required luck.

Even today, after all that effort, Iraq remains fragile. Its institutions function, but unevenly. Its democracy exists, but it is incomplete and contested. It survives—but not granteed and survival is not the same as stability.

The human cost was immense. Civilians paid first and longest. Institutions paid in credibility and continuity. The state was perhaps the hardest casualty to repair.

This is the part that is often misunderstood from afar: foreign intervention externalises the decision, but internalises the chaos. The bombs fall from outside, but the fragmentation unfolds within.

State collapse is not a transition. It is a cross-generational trauma.

Democracy Is Negotiated: It Is Long, Painful, and Hard

The most enduring democracies of the late twentieth century did not emerge from total collapse. They emerged from negotiation.

This is not an abstract claim. It is one of the central findings of comparative political science. Scholars of democratic transition—from Guillermo O’Donnell and Philippe Schmitter to Juan Linz and Alfred Stepan—have shown that stable democracies most often arise through what they called “pacted transitions”: negotiated transformations between reformist elements within the state and organised forces within society. Democracy is not imposed; it is bargained into existence.

The Evidence of Negotiated Transitions

Consider Spain after Franco. The dictatorship did not fall through foreign invasion or armed revolution. It evolved through internal elite splits, reformist factions within the regime, and negotiations with opposition forces. The 1978 Constitution was the product of compromise—imperfect, painful compromise. But Spain avoided civil war, preserved institutional continuity, and transitioned into a stable democratic order. Spain tried revolution a few decades before. After about three years of civil war and after a million people were killed, Republicans surrendered to the forces of General Franco in 1939, and he was able to establish a dictatorial government similar to the fascist regime throughout the country.

Chile after Pinochet followed a similar path. The regime did not collapse militarily. It was pressured—internally and externally—into accepting a referendum. Opposition groups mobilised civil society, but the transition preserved key state institutions. The military was not dismantled overnight. The bureaucracy did not implode. The result was gradual democratisation without state disintegration.

South Africa’s transition from apartheid remains perhaps the most striking example. The African National Congress and the ruling National Party entered negotiations despite decades of violence. The outcome was not revolutionary justice. It was negotiated power-sharing, constitutional reform, and institutional continuity. It prevented civil war. It preserved territorial integrity. It created the framework for democratic consolidation.

In each case, democracy did not emerge from the ashes of total collapse. It emerged from structured bargaining.

Negotiation works not because it is morally superior, but because it is structurally stabilising.

1. It avoids total institutional collapse.

When armies, courts, and bureaucracies remain functional—even if reformed—society avoids the vacuum that armed actors rush to fill.

2. It preserves administrative continuity.

Governance is not rebuilt from zero. Services continue. Borders remain managed. The state remains recognisable.

3. It reduces civil war risk.

By incorporating former regime elements into the new order, negotiation lowers the incentive for violent spoilers to fight to the end.

4. It protects territorial integrity.

Collapse invites fragmentation. Negotiation maintains a single political arena within which conflict can be institutionalised rather than militarised.

Political theorists call this the transformation of conflict from violent to institutionalised competition. Democracy does not eliminate struggle; it relocates it into procedures.

Negotiated transformation is not passive. It demands structural conditions:

• Internal political actors capable of bargaining.

• Civil society pressure strong enough to demand reform but disciplined enough to avoid total breakdown.

• Elite splits within the ruling system that open space for compromise.

• Gradual institutional reform rather than instant purification.

It requires patience and restraint—qualities rarely celebrated in revolutionary moments.

Why It Feels Unsatisfying

Negotiation rarely produces catharsis.

There is no dramatic overthrow.

No moral spectacle of total victory.

No instant justice.

France VS Britain Example

Compromises offend purists. Former regime actors survive politically. Transitional justice may be incomplete. The pace feels slow. Anger feels unfulfilled.

But that very dissatisfaction is often the price of stability.

Revolutions promise moral clarity. Negotiations produce durable systems.

A useful historical contrast is France and Britain in the long transition from absolutist monarchy to modern democracy.

France chose rupture. The 1789 Revolution dismantled the ancien régime through mass mobilisation and violence. It abolished feudal structures, executed the king, and declared a new political order. But the revolutionary path also unleashed cycles of radicalisation—the Reign of Terror, factional purges, counter-revolutionary wars, and eventually Napoleon’s military dictatorship. Over the next century, France experienced repeated regime breakdowns: empire, restoration, republic, empire again, and more instability before democratic institutions consolidated. The revolution destroyed the old order decisively—but at immense human cost, institutional collapse, and decades of political turbulence.

Britain followed a slower, negotiated path. There was no single dramatic revolutionary rupture in the modern era. Instead, power shifted gradually through reform acts (1832, 1867, 1884), expansion of suffrage, parliamentary bargaining, and incremental curbing of monarchical authority. Elites compromised rather than annihilated one another. Institutions were reformed, not dismantled. The cost was frustration and inequality that persisted for long periods—but the benefit was continuity, relative stability, and the avoidance of large-scale political violence.

The comparison does not suggest that Britain was morally superior or that France’s revolution was unnecessary. Rather, it highlights structural differences in transition paths. France achieved rapid symbolic transformation but endured prolonged instability. Britain moved slowly, often imperfectly, but preserved institutional continuity and avoided repeated systemic collapse.

In short: France won a revolution and paid for it in blood and instability; Britain negotiated reform and paid for it in patience and compromise. Both eventually built democracies—but the routes, costs, and timelines were profoundly different.

The Structural Lesson

Comparative evidence is consistent: where regimes collapse through external force or uncontrolled uprising, institutional destruction often precedes democratic possibility. Where transitions are negotiated, democracy stands a chance.

This is not a romantic argument. It is a structural one.

Democracy requires:

• Institutional continuity

• Political bargaining

• Social contracts

• A monopoly of violence under law

War and collapse undermine each of these foundations.

The temptation of revolutionary rupture is powerful, especially under repression. But the evidence suggests that societies survive—and eventually democratise—when transformation is negotiated rather than detonated.

Democracy is not a moment. It is a process.

Excellent, instructive article - a great read.

The fallacy of the assumption that "anger will translate into cohesion" may seem easy to point out, but captures the central ambiguity of violent change very well - whether "home-grown" or induced from afar.

Is the American revolution an exception? Well, some prominent Americans have thought everything about America is exceptional. Strobe Talbott in 1995, summing up why post-Soviet Russia would have to fit in with the superior ways of the American century: "That's us, that's the US: We are exceptional."

But maybe a quirky analysis could also be made of the institutional consequences of the putatively exceptional American revolution. I.e. it's apparent niceness was followed by the formalisation of a constitutional, presidential and electoral college system that's pretty weird, and (especially the electoral college) remains weirdly anchored to the historical moment when the states became united. I.e. nice revolution and nice break with colonial status, but pity about the way the country' democracy has ended up.

In case of use, Jacques Rancière's "Hatred of Democracy" is a short and racy return to some of the tricky bits at the bottom of the democratic machine:

https://www.versobooks.com/en-gb/products/1990-hatred-of-democracy?srsltid=AfmBOopxiuWCWrf61eY-m0cRTJEEoSrMeZMTJTgqZ4qnAaz6dIjijVGj

And:

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.oddweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Ranci%25C4%258Dre-Hatred-of-Democracy.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjnhYDcpdOSAxW5T_UHHegzC9YQFnoECFQQAQ&usg=AOvVaw2JrUPDhxSdwuRylseXWBHL