Arming Iranian Protesters: What Would Actually Happen?

In moments of brutal repression, a familiar proposal resurfaces: arm the protesters. As images of violence circulate and moral outrage peaks, some policymakers and commentators frame weapons as a shortcut to regime change in Iran. The appeal is obvious—but the question is unavoidable. Does arming civilians lead to liberation, or does it drag societies into something far worse? History offers a sobering answer: externally militarised uprisings rarely end authoritarianism cleanly. Far more often, they dismantle states, fracture societies, and replace one form of authoritarianism with another.

Who Is Calling for Arming the Protesters?

Calls to arm Iranian protesters are not emerging from the margins alone. They have been articulated openly by senior political figures, amplified by media outlets, and echoed by opposition voices abroad—often in moments of peak emotional intensity following reports of state violence.

In the United States, Senator Ted Cruz (R–Texas) made one of the most explicit interventions. Responding to reports of repression during the protests, Cruz wrote on X: “We should be arming the protesters in Iran. NOW.” The statement marked a shift from rhetorical support for protests to an overt call for militarisation.

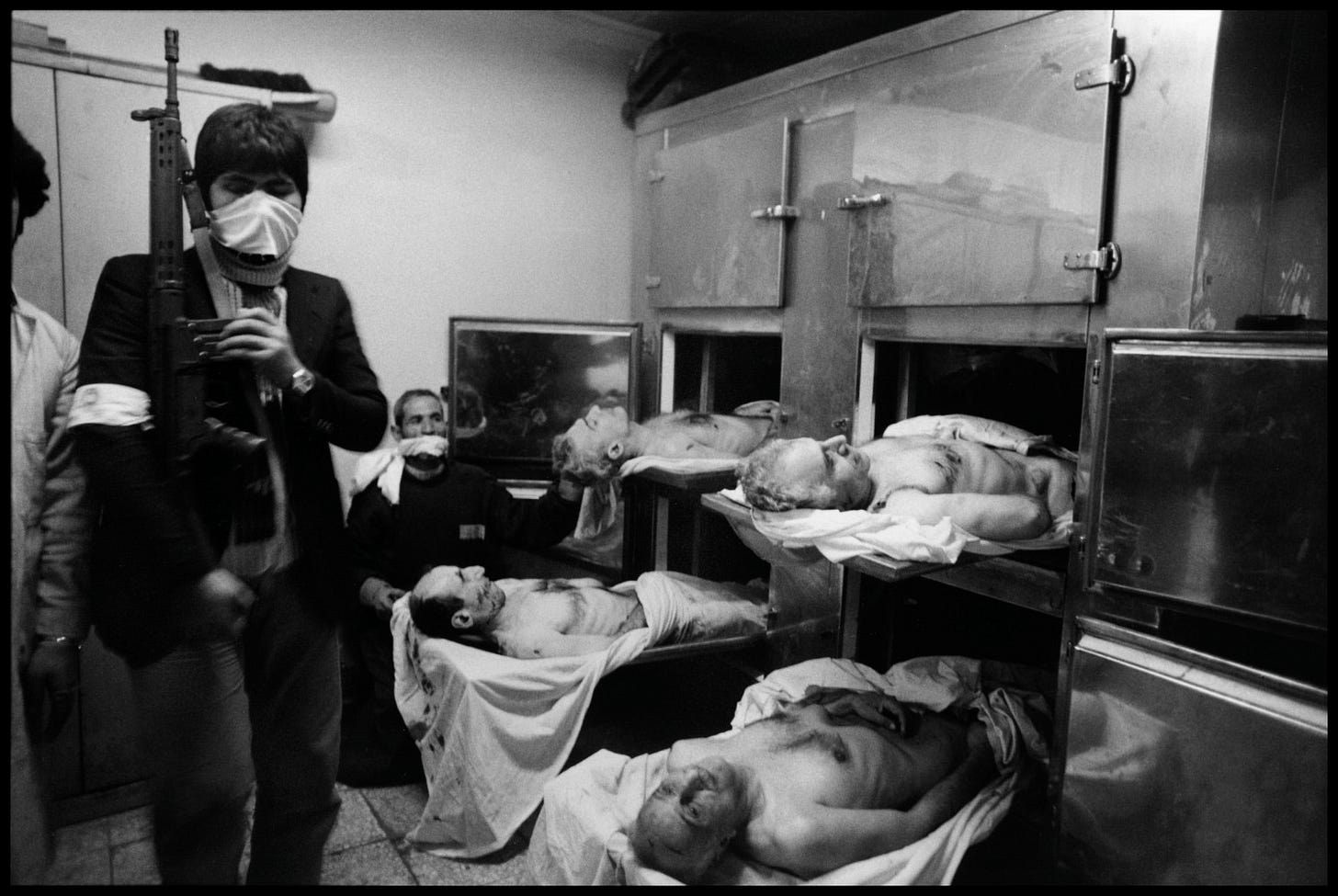

Cruz’s post came in reaction to a widely circulated thread by “Tehran Bureau”, which described alleged mass atrocities during the crackdown, including claims of 20,000 to 30,000 people killed, beheadings, and large-scale executions. Many of these allegations including the figures were later disputed or revised downward by more reliable human rights reporting, with the highest credible estimates placing deaths in the range of several thousand rather than tens of thousands. The same thread concluded with a stark assertion: that peaceful protest had become impossible without arms, arguing that gathering was futile unless protesters were “armed like them.” The emotional force of such claims played a key role in normalising the idea of weaponisation as a necessary response.

Similar narratives appeared in Israeli media. During the protests, Channel 14 reported that foreign actors were allegedly supplying Iranian protesters with live firearms, attributing the deaths of regime personnel to armed resistance. While no independent evidence substantiated these claims, the implication was clear: that covert external involvement was already underway. The channel left the identity of these actors to speculation.

Former U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo also contributed to this atmosphere of ambiguity. In a New Year’s message posted on X, he wrote: “Happy New Year to every Iranian in the streets. Also to every Mossad agent walking beside them.” When later asked in an interview whether the United States had helped protesters—following statements by then-President Trump suggesting that “help is coming”—Pompeo responded that assistance had indeed been provided, even if it was not visible. While he did not specify the nature of that help, the implication of covert support, possibly including arms, was widely inferred.

Beyond official statements, calls for militarisation have also come from segments of the Iranian opposition abroad, particularly pro-monarchy groups. Some activists outside Iran openly demanded foreign military intervention, called for weapons to be supplied to protesters, and issued threats of violent retribution against regime supporters, including language advocating executions and collective punishment in a post-regime scenario.

Taken together, these voices illustrate how quickly moral outrage can slide into advocacy for armed escalation. What begins as solidarity with civilian protesters can transform into a narrative that frames weapons not as a tragic last resort, but as the primary solution—often without serious engagement with the historical consequences of turning mass protest into civil war.

Iran’s Own Historical Memory: The Shadow of 1979

For Iranians, the idea that weapons can liberate society is not abstract theory—it is lived history. The 1979 Iranian Revolution is often remembered as a broad-based civilian uprising, and in its initial phase that description is largely accurate. The Shah left the country, the military fractured and then largely stood aside, and power transferred with far less immediate bloodshed than many revolutions. Yet what followed offers a far more cautionary lesson.

The collapse of the old order was quickly followed by rapid militarisation. Armed factions proliferated across the country as competing visions of Iran’s future moved from politics to force. Separatist uprisings erupted in Kurdistan, Baluchistan, and Khuzestan. The Mujahedin-e Khalq and other armed groups turned against the new leadership, carrying out bombings, assassinations, and street-level violence. What had begun as a popular revolution slid into years of internal armed conflict, insecurity, and repression.

This environment did not produce pluralism or democratic consolidation. It produced the opposite. Armed struggle rewarded organisation, discipline, and ideological rigidity—not popular legitimacy. Revolutionary committees, militias, and parallel security structures emerged, gradually eclipsing civilian institutions. Among them, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) proved the most coherent, unified, and strategically positioned actor.

Crucially, militarisation enabled the consolidation of power. The IRGC grew not simply as a military force, but as a political, economic, and intelligence institution embedded at the core of the state. The logic of permanent threat justified permanent securitisation. Dissent became synonymous with subversion, and the revolution hardened into a new authoritarian order.

The lesson is stark. Weapons did not empower Iranian society; they empowered those best positioned to monopolise violence. In revolutionary environments, arms do not level the playing field—they tilt it decisively toward actors with ideological cohesion, command structures, and external backing. The shadow of 1979 serves as a reminder that militarising protest does not dismantle authoritarianism; it often rebuilds it in a more durable form.

Regional Precedents: When Uprisings Become Proxy Wars

The call to arm protesters does not emerge in a historical vacuum. Across the Middle East, recent uprisings offer stark evidence of what happens when popular protest is militarised by external actors. Syria and Libya stand as the clearest warnings—not because their contexts were identical to Iran’s, but because the dynamics that followed external arming were tragically consistent.

A. Syria

When protests began in Syria in 2011, they were overwhelmingly peaceful. Demonstrations cut across social classes and sects, and for months protesters demanded reform rather than regime collapse. The turning point came when the uprising was militarised—first internally, then externally.

Foreign arms did not unify the opposition; they fragmented it. Competing factions emerged, each backed by different regional and international sponsors, each pursuing its own agenda. Ideology hardened, sectarian identities were weaponised, and jihadist groups flourished in the chaos. What followed was not liberation, but civil war.

The consequences were devastating: mass displacement, foreign military intervention, the destruction of state institutions, and the entrenchment of sectarian violence. ISIS rose directly out of this environment. Yet after more than a decade of bloodshed, one fact remains unavoidable—the Syrian regime survived for another 13 years. It did so at the cost of society itself. The state was hollowed out, sovereignty compromised, and millions of Syrians displaced or killed. The war destroyed the country without achieving the political outcome its early supporters promised.

B. Libya

Libya offers a different but equally instructive trajectory. Here, international militarisation came swiftly. NATO intervention helped topple Muammar Gaddafi in a matter of months. The regime fell—but nothing replaced it.

There was no post-conflict political architecture, no unified security sector, and no mechanism for national reconciliation. Armed groups filled the vacuum, each claiming legitimacy through force. Militias became power brokers. Competing governments emerged. Foreign actors entrenched themselves through proxies. Libya lost not only its regime, but its sovereignty.

More than a decade later, the country remains trapped in chronic instability. Elections fail, institutions fracture, and violence remains a recurring tool of politics. The lesson is blunt: removing a regime is not the same as preserving a state. In Libya’s case, the former destroyed the latter.

Together, Syria and Libya illustrate a hard truth often ignored in moments of moral urgency. When uprisings become proxy wars, societies pay the price. External arms (in the form of armed protests or foreign intervention) rarely if not never deliver democracy. They deliver fragmentation, warlordism, and long-term instability—while regimes either survive or are replaced by something no less coercive.

What Arming Protesters Would Do to Iran

Calls to arm Iranian protesters often assume a simple escalation: weapons balance power, power forces change. In reality, Iran’s internal conditions make such an outcome not only unlikely, but dangerous.

Iran is not a fragile or hollowed-out state. It is a densely governed society with deep internal fault lines—ethnic, sectarian, regional, and ideological—that have been managed, instrumentalised and sometimes suppressed over decades. Kurdish, Baluchi, Arab, religious, and secular grievances coexist within a highly securitised system. Introducing weapons into this environment would not unify resistance; it would expose and inflame these divisions.

The state itself is exceptionally prepared for internal conflict. Iran possesses one of the most sophisticated domestic security and intelligence apparatuses in the region, refined through decades of counterinsurgency, surveillance, and population control. It has also accumulated extensive experience running proxy warfare beyond its borders—from Lebanon to Iraq, Syria, and Yemen. A state that has mastered the art of fragmented warfare abroad would have little difficulty managing, infiltrating, and ultimately exploiting armed fragmentation at home.

The most immediate outcome of arming protesters would be the fragmentation of the opposition itself. Competing armed groups would emerge, each claiming legitimacy, each shaped by local dynamics and external patrons. Political demands would quickly give way to military calculations. Leadership would flow to those who control weapons, not those with broad social support or political vision.

Militarisation would also hand the state its most powerful justification: total repression. Peaceful protest challenges legitimacy; armed resistance legitimises overwhelming force. Once weapons enter the streets, the conflict shifts from a struggle between society and the state to violence within society itself. Protest becomes civil conflict. Dissent becomes insurgency. The moral and political high ground is lost.

In this environment, the beneficiaries are rarely the people who first took to the streets. Armed factions gain leverage. Foreign intelligence services gain access and influence. Regional rivals gain opportunities to weaken Iran from within. What disappears is civilian protection, political coherence, and the possibility of a negotiated or unified transition.

The losers are predictable and consistent across history: protesters who sought dignity rather than war, civilians caught between armed actors, and any realistic chance of a national political project capable of replacing authoritarian rule with something better.

Arming protesters does not shorten the path to freedom—it reroutes it through chaos, bloodshed, and outcomes that history has already shown to be far worse than the status quo.