Winning Wars, Losing Souls: When Victory Becomes Defeat

The Jewish historian Yuval Noah Harari recently described Israel’s war against the Palestinians as nothing less than a historic rupture—a “turning point” that could redefine not only the future of Israel but the very meaning of Judaism itself. Speaking on Unholy, Harari warned that the present moment may mark “the biggest turning point in Jewish history since the fall of the Temple in 70 CE, since the Roman conquest.”

He called it a “spiritual catastrophe for Judaism,” one that threatens to erase two millennia of Jewish thought, culture, and identity. According to Harari, three forces are converging to produce this moral crisis: “the potential ethnic cleansing of Gaza and the West Bank” through the forced displacement of millions, the pursuit of a “Greater Israel,” and the “disintegration of Israeli democracy” itself.

History is full of such paradoxes. Nations and empires have often won wars on the battlefield only to lose the deeper struggle for moral legitimacy and collective memory. The victors can crush bodies, but in doing so they risk forfeiting their soul—and with it, their place in history and their future existence.

This tension between military triumph and moral collapse lies at the heart of the question of what it means to “win.” History repeatedly shows that while armies may conquer territory, it is the loss of moral legitimacy that ultimately determines whether a victory endures or dissolves into long-term defeat.

Rome and Christ: A Victory That Became Defeat

When Christ emerged in the Holy Land, he stood as a solitary figure with a handful of powerless followers, armed only with a message of faith and a vision to transform human civilization. Standing against him were two formidable powers: the Roman Empire, which ruled vast territories across Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia, and the Jewish religious establishment, deeply entrenched in its authority.

At the time, the survival of his message seemed not only improbable but almost absurd. By contrast, the collapse of the Roman Empire or the removal of the Jewish people from their land appeared unthinkable. Yet history unfolded differently. Within just four decades, the Jewish people were expelled from Jerusalem after Titus Caesar Vespasianus destroyed the Temple in 70 CE. And within 350 years, the Roman Empire itself dissolved—not by external conquest, but by absorbing and being transformed from within by Christianity, the very faith it once sought to crush.

Another powerful example comes from early Islamic history: the martyrdom of Imam Hussein at Karbala. Though militarily defeated by one of the most powerful caliphates of the time, his sacrifice profoundly shaped the course of Islamic history, undermining the moral legitimacy of the Umayyads and leaving an enduring legacy that outlasted their rule.

In 680 CE, on the plains of Karbala, Imam Hussein, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, stood with a small group of family members and followers against the vastly superior forces of the Umayyad caliph Yazid. Militarily, the confrontation was never a contest; Hussein and his companions were surrounded, deprived of water, and brutally massacred. From the perspective of worldly power, the Umayyads had secured an undeniable victory.

Yet history did not vindicate Yazid. What appeared to be a triumph of empire became a moral and spiritual defeat. The blood of Hussein transformed into a symbol of resistance against tyranny and injustice, inspiring generations of Muslims and shaping the conscience of Islam itself. Karbala marked a turning point: while the Umayyads maintained political dominance for a time, their legitimacy was fatally compromised. Hussein’s martyrdom lived on as a force far greater than the battlefield, carried in rituals, literature, and collective memory, ensuring that his message endured long after the Umayyad dynasty crumbled.

The victories achieved through the abandonment of moral restraint are, at best, temporary illusions of power. While the immediate victims bear the trauma of violence and dispossession, the perpetrators, too, inherit a lasting burden—a collective moral rupture that corrodes their legitimacy and, over time, destabilizes their own historical foundations. A triumph secured through catastrophe plants the seeds of its own undoing, ensuring that what appears as conquest in the moment becomes remembered as moral failure in the longue durée of history.

A Crisis of the Jewish Spirit

For centuries, Jews endured persecution, displacement, and attempts at extermination—including genocidal campaigns that sought to erase them from history. Yet, against overwhelming odds, they survived while many of their oppressors disappeared into the dust of history.

Harari draws on this very legacy to highlight the profound irony of the present moment: a people once celebrated as the “world champions of survival” have, in his words, shifted into becoming exceptional suppressors. He warns that the foundations of the modern State of Israel are increasingly tied not to resilience and moral witness, but to “Jewish supremacy and the worship of power and violence.”

Israel today is militarily powerful, allied with global powers, and economically robust. Yet beneath this strength lies what Harari describes as an existential threat to the nation’s spiritual core—a moral rupture that risks corroding Jewish identity from within. This is not merely a political crisis but, as he terms it, a “spiritual catastrophe,” one that could unravel two millennia of Jewish cultural and ethical legacy.

Contemporary polls reveal that roughly half of Israelis fully endorse the war in Gaza, while 70–80 percent support the complete displacement of Palestinians from Gaza and the West Bank. Militarily and politically, Israel has already advanced many of its objectives: devastating Gaza through relentless bombardment, imposing famine-level deprivation, expanding settlements across nearly every corner of the West Bank, and even extending its reach into Syrian territory while launching strikes across the region. These policies have inflicted profound suffering on Palestinians and destabilized the region.

Yet the central question remains: can a nation sustain itself while carrying the weight of such actions? Will military successes and territorial gains bring relief, or will the moral burden of these choices erode Israel’s spiritual foundation, leaving a legacy not of triumph but of internal disintegration?

Can Victory Survive Without Morality?

Evil does not arise only from extraordinary villains; it emerges from ordinary people. As Friedrich Nietzsche observed, the will to power is a fundamental human drive, and under certain conditions, it can manifest in destructive, even catastrophic ways. Hannah Arendt, the great Jewish philosopher who survived the Holocaust, took this further in her theory of the “banality of evil.” She argued that atrocities are often carried out not by fanatics or sociopaths, but by seemingly ordinary individuals who fail to think critically, conform to dominant ideologies, and rely on clichés instead of moral judgment. In her view, systems of power normalize and bureaucratize evil, rendering it more insidious, more pervasive, and harder to resist.

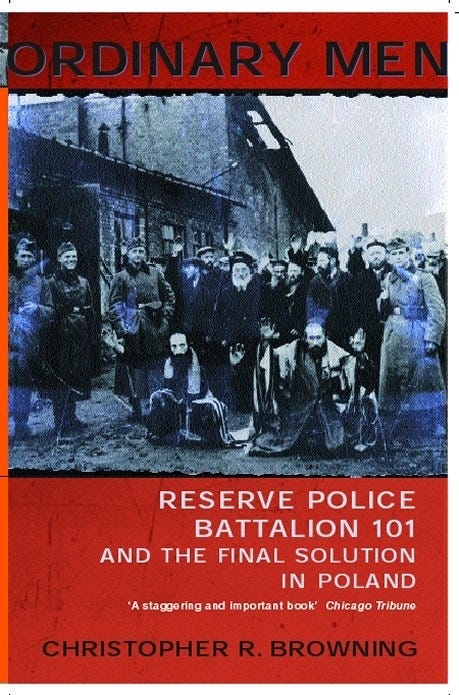

Christopher Browning’s seminal work Ordinary Men provides historical evidence of this claim. He demonstrates how regular, otherwise unremarkable German men became participants in mass atrocities under the Nazi regime—not because they were inherently monstrous, but because they were absorbed into a bureaucratic system designed to channel obedience into organized destruction.

The relevance to the present is clear: Israel’s trajectory raises the question of whether a nation can survive when its political and military power risks becoming detached from morality. Can a state continue to endure while inflicting collective punishment, displacement, and destruction, even if it secures short-term victories? Or does such a path inevitably erode not only the moral foundation of the nation, but the very spiritual and historical continuity of Judaism itself?

History and millennia of human tradition alike suggest that no power is invincible when it loses its moral compass. The example of the Night King in Game of Thrones—a seemingly indestructible leader commanding an army of the dead—offers a cultural parable: he was ultimately undone not through brute force, but by a strike from an unexpected place, a vulnerability he could neither predict nor defend against. Likewise, a nation that believes itself invulnerable may one day collapse, not from external defeat, but from an inner moral implosion it failed to foresee.