Why Iran’s Uprising Is Not a Revolution Yet?

Regimes do not fall when people hate them; they fall when power structures crack.

Iran is once again in the grip of mass protest, with scenes of defiance and confrontation echoing across the country. To many outside observers, it looks like the prelude to another 1979—a society rising up to sweep away a deeply unpopular regime. Yet history and political theory suggest a more complicated reality. While anger is widespread and legitimacy has eroded, revolutions are not born from rage alone. Understanding whether today’s unrest can become a true revolution requires looking beyond the streets, to the structures of power, fear, and fragmentation that still hold the Islamic Republic together.

What Makes a Revolution?

Political science has long tried to explain why some uprisings lead to the collapse of regimes while others, even when massive and sustained, do not. Across different schools of thought, a central insight emerges: revolutions are not simply the result of anger or hardship. They are the outcome of specific structural, social, and political breakdowns that converge at a particular moment.

Classical materialist theories, most famously associated with Karl Marx, view revolutions as the product of deep economic contradictions. When exploitation becomes unsustainable and class divisions harden, the system eventually breaks. Later thinkers such as Lenin extended this logic to geopolitics, arguing that imperial pressure and uneven development make certain states more vulnerable to revolutionary collapse. But economic suffering alone has rarely been enough; many poor societies do not revolt, while some revolutions erupt in countries that were improving economically before they collapsed.

Psychological approaches focus less on poverty and more on expectations. The theory of relative deprivation, associated with Ted Gurr, argues that revolutions happen when people experience a sharp gap between what they believe they deserve and what they actually receive. When societies rise, develop hope, and then suddenly face decline, frustration becomes explosive. In these moments, anger is directed not just at conditions, but at the political system seen as having betrayed its promises.

Structural theories, developed by scholars such as Theda Skocpol go even further. They show that mass protests alone do not topple regimes. Revolutions succeed when the state itself becomes weak—when institutions fracture, when elites split, and when the security forces can no longer reliably enforce order. Without these cracks at the top, even enormous popular movements can be contained.

Elite theories reinforce this point: regimes fall when ruling coalitions break apart and no longer agree on how to rule or who should rule.

Modern scholarship brings these elements together. Successful revolutions require not only grievance, but also leadership, ideology, organizational capacity, elite defection, and often international conditions that prevent the state from crushing opposition.

This framework is crucial when evaluating today’s unrest in Iran. While frustration, economic pressure, and anger at the system are undeniable, revolutions do not emerge simply because a society is unhappy. They emerge when the political order itself begins to disintegrate from within. Whether Iran has reached that point is the central question the rest of this analysis will address.

The 1979 Revolution: What Was Different?

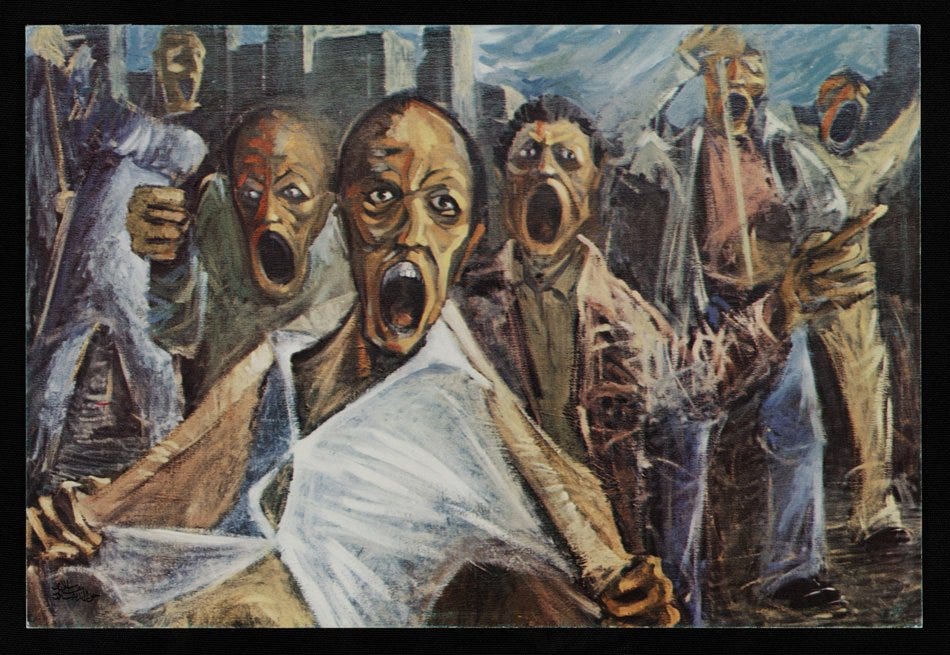

To understand why Iran’s current uprising is not a revolution, it is essential to recall why the 1979 Islamic Revolution succeeded. Revolutions are not just about anger or protest; they are about the collapse of an entire political order. In 1979, nearly every condition required for regime breakdown converged at once.

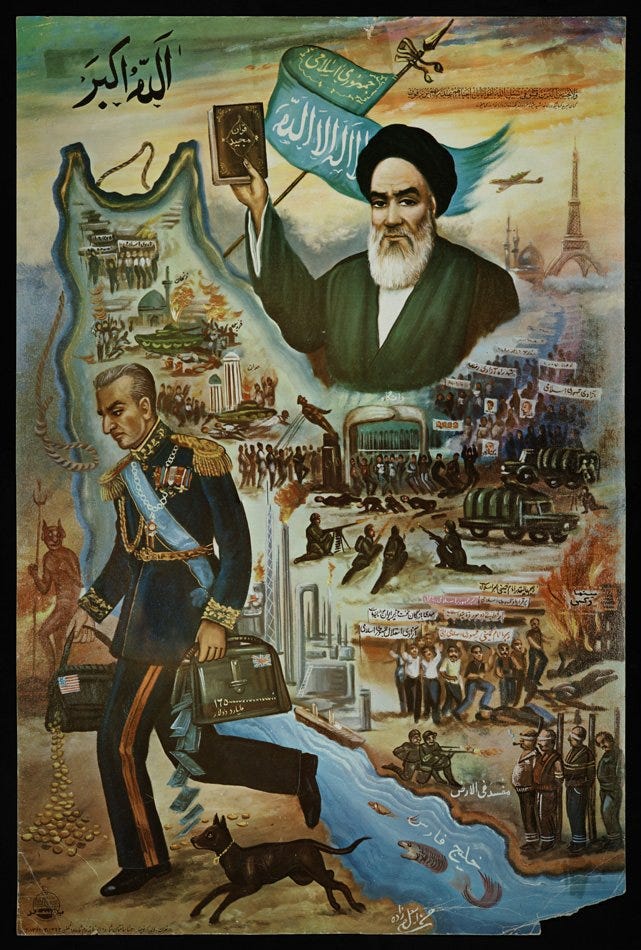

First, the Shah faced a unified national narrative against him. Very different social forces — Islamists, leftists, liberals, bazaar merchants, students, workers, and clerics — all rallied behind a shared story: the monarchy was corrupt, dependent on foreign powers, and morally bankrupt. Anti-imperialism, social justice, Islamic identity, and political freedom became fused into one powerful national message. The Shah was not just unpopular — he was seen as illegitimate.

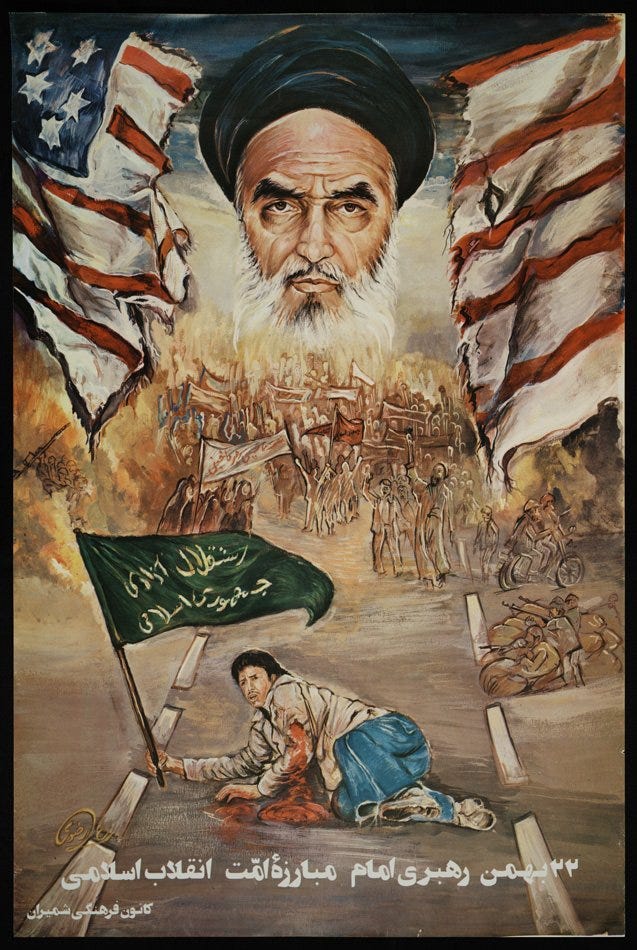

Second, the opposition had clear leadership and symbolic authority. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was not just a political figure; he was a religious authority with deep roots across Iranian society. He gave the revolution coherence, discipline, and moral legitimacy. Protesters did not just chant against the Shah — they rallied for Khomeini. This provided the movement with unity, direction, and a vision of what would replace the monarchy.

Third, the state’s coercive power fractured. In the final weeks of the revolution, the Iranian army refused to fire on demonstrators. Senior officers declared neutrality. Some units even defected. Once the military stopped defending the Shah, the regime collapsed almost overnight. No authoritarian system can survive when its armed forces withdraw loyalty.

Fourth, Iran experienced economic paralysis through mass strikes. Oil workers, civil servants, transport workers, and bazaar merchants shut down the country. The state could not pay salaries, export oil, or maintain basic governance. The economy was not just suffering — it had stopped functioning. This deprived the Shah of revenue and control.

Fifth, there was elite defection. Business leaders, technocrats, and even parts of the royal court abandoned the monarchy as they sensed it was losing. They did not defend the system; they prepared for its replacement.

Finally, there was a deep social and economic rupture. Rapid modernization under the Shah had widened inequality, uprooted traditional communities, and created a vast, frustrated middle and lower class. Rising expectations met sudden political repression, creating the perfect conditions for revolutionary anger.

In short, the 1979 revolution was not merely a protest wave — it was a systemic collapse driven by unified ideology, organized leadership, economic shutdown, elite desertion, and the breakdown of military loyalty. That historical benchmark is what makes clear how fundamentally different today’s unrest really is.

Why the Regime Is Still Standing?

The answer to this question lies in the answer to another question that why anger does not automatically become revolution?

Iran today is experiencing one of the deepest waves of social anger in its modern history, yet that anger has not crossed the threshold into a revolutionary rupture. The gap between grievance and revolution is explained not by the absence of outrage, but by the continued strength of several stabilizing mechanisms inside the state and society.

First, protests are widespread but structurally contained. Unlike 1979, when strikes shut down oil exports, banks, transportation, and the bureaucracy, today’s protests remain socially deep but economically shallow. Bazaar merchants, industrial workers, energy sectors, and civil servants—groups that once paralyzed the Shah’s state—have not joined in sustained national strikes. Without economic paralysis, the regime continues to function, pay salaries, operate security forces, and maintain basic governance. Anger fills the streets, but the system’s circulatory system has not stopped.

Second, the security architecture remains intact and loyal. The Islamic Republic does not rely on a single army. It operates a layered security system: the IRGC, Basij, intelligence agencies, police, and parallel military structures that monitor one another. Unlike the Shah’s military, which fractured and ultimately went neutral, Iran’s forces have shown no sign of elite defection or internal split. Even after Israeli infiltration and strikes, the system quickly reconstituted itself and purged suspected penetrations. Revolutions require elite fracture; Iran’s security elite remains unified.

Third, the opposition is fragmented and strategically hollow. There is no single leadership, no unified narrative, and no recognized alternative government. Inside Iran, protests lack organizational coherence. Outside Iran, the diaspora is divided between royalists, the MEK, reformists, and activists who distrust each other as much as they oppose the regime. Unlike 1979, when Khomeini served as a symbolic and organizational center of gravity, today there is no figure capable of converting protest into power.

Fourth, fear restrains society more than belief sustains the regime. Many Iranians no longer support the system ideologically, but they also do not trust what comes after it. Iraq, Syria, Libya, and Afghanistan loom large in the public imagination. The regime has successfully reframed collapse as chaos, and for millions of Iranians, the risk of state failure outweighs the hope of political change. This fear freezes potential mass mobilization even when legitimacy has eroded.

Finally, the regime still possesses money and institutional survival tools. Despite sanctions, Iran continues to sell roughly two million barrels of oil per day through shadow networks, barter systems, cryptocurrency, and front companies. These revenues fund security forces, social subsidies, and elite loyalty. Unlike collapsed states, Iran is not financially starved. It remains capable of sustaining repression and basic economic circulation.

In short, Iran has lost belief but not control. Its narrative is broken, but its coercive, financial, and institutional foundations remain intact. History shows that regimes do not fall when people hate them; they fall when power structures crack. That moment has not yet arrived.