When Solidarity Becomes a Liability: How Parts of the Iranian Diaspora Are Damaging Iran’s Protest Movement

Introduction: The Diaspora Paradox

The latest wave of protests in Iran has generated unprecedented global attention. Much of that visibility has been driven by Iranian diaspora activism—through media appearances, social platforms, lobbying efforts, and sustained online campaigning. From raising awareness to mobilising international solidarity, diaspora networks have played a central role in keeping the uprising in the global spotlight.

Visibility, however, does not automatically translate into effectiveness. Attention can amplify a movement, but it can also distort it—especially when narratives are shaped far from the conditions, risks, and constraints faced by protesters on the ground. The distance that allows diaspora actors to speak freely can also encourage strategic overreach, rhetorical escalation, and simplified framings that do not reflect the complex realities inside the country.

This raises a central question: has diaspora activism begun to distort, radicalise, or instrumentalise a movement it claims to support? While often driven by genuine solidarity and moral urgency, parts of the diaspora have amplified harmful narratives, escalated rhetoric, and promoted strategies whose costs are borne almost entirely by protesters inside Iran. In doing so, they may have unintentionally strengthened the regime’s repression and reinforced its efforts to delegitimise the uprising as foreign-driven.

Understanding this paradox is essential—not to dismiss diaspora engagement, but to assess how certain forms of activism can undermine the very movement they seek to advance.

1. The Structural Distance Problem

A defining feature of diaspora activism is distance—physical, political, and psychological—from the conditions of repression inside Iran. This distance allows diaspora voices to speak freely, organise openly, and advocate publicly without facing the immediate risks that confront protesters on the ground. While this freedom is a powerful asset, it also produces a structural imbalance that shapes how strategies and narratives are formed.

The result is an asymmetry of risk. Protesters inside Iran face arrest, surveillance, loss of livelihood, collective punishment, and lethal force. Diaspora activists, by contrast, bear few direct consequences for calls to escalate confrontation, reject compromise, or invite external pressure. Decisions and rhetoric generated abroad therefore impose costs that are paid almost entirely by others.

This imbalance often encourages maximalist positions. Distance reduces sensitivity to incremental gains, tactical retreats, or nonviolent endurance, and instead rewards absolute demands—immediate regime collapse, armed resistance, or foreign intervention. Social media further amplifies this tendency by privileging dramatic language, moral certainty, and escalation over restraint or strategic patience.

In this way, distance does not merely separate diaspora activists from events inside Iran; it reshapes their strategic calculus. What appears bold or principled from afar can translate into miscalculation on the ground—raising expectations that cannot be met, escalating violence that cannot be sustained, and narrowing the space for adaptive, locally grounded forms of resistance.

2. The Agency Problem: Who Speaks for Protesters?

A second, closely related challenge is the agency problem: who gets to speak on behalf of the protest movement, and with what legitimacy. As international attention has grown, diaspora figures—activists, commentators, former officials, and self-appointed representatives—have increasingly positioned themselves as the authoritative voices of the uprising. Through access to global media, policy circles, and social platforms, these actors often shape how the protests are interpreted abroad.

This dynamic risks reducing protesters inside Iran to political assets rather than political subjects. Their diverse motivations, tactical debates, and local constraints are flattened into simplified narratives that fit external agendas or media expectations. Protesters become evidence to be cited, images to be circulated, or sacrifices to be invoked—rather than agents capable of articulating their own priorities and limits.

Media incentives reinforce this imbalance. Journalists and policymakers often prefer readily available, English-speaking sources who can provide clear, emotionally compelling narratives on demand. Exile voices, unburdened by censorship or personal risk, naturally fill this role. Meanwhile, voices from inside Iran—fragmented by internet shutdowns, repression, and security concerns—struggle to be heard or sustained.

The consequence is a growing gap between representation and reality. As diaspora elites dominate the narrative space, the movement’s direction appears increasingly shaped from outside, raising questions about whose interests are being advanced and whether the agency of those risking their lives on the ground is being overshadowed rather than amplified.

3. Narrative Warfare and Diaspora Amplification

Diaspora networks play a central role in the production and dissemination of narratives surrounding the protests. Through social media platforms, satellite television, podcasts, and international media appearances, diaspora actors often become key intermediaries between events inside Iran and global audiences. In this process, many function—often unintentionally—as force multipliers in psychological warfare, amplifying certain framings while marginalising others.

Two dynamics are particularly significant. First is the amplification of simplified and absolutist narratives. Complex social movements are reduced to binary stories of total revolution versus total repression, leaving little room for ambiguity, internal disagreement, or tactical diversity. Second is the suppression of nuance and internal debate. Voices that question escalation, reject violence, or caution against foreign intervention are frequently dismissed as naïve, compromised, or disloyal.

These tendencies are reinforced by the architecture of social media itself. Platforms reward content that provokes outrage, offers moral certainty, and signals escalation. Messages that are emotionally charged, confrontational, or absolutist travel further and faster than those that are cautious or analytically grounded. As a result, strategic considerations—such as sustainability, risk management, or the preferences of protesters on the ground—are often overridden by the pursuit of visibility and engagement.

In this environment, narrative warfare becomes self-reinforcing. Diaspora amplification does not merely reflect events inside Iran; it actively reshapes how those events are understood, evaluated, and responded to. The danger lies not only in distortion, but in the narrowing of the political imagination—where only the most extreme framings appear legitimate, and alternative paths are crowded out before they can be seriously considered.

4. Radicalising the Movement: Escalation Rhetoric and the Cost of Violence

One of the most consequential effects of diaspora-driven narrative amplification has been the radicalisation of protest discourse, particularly through rhetoric that normalises or actively promotes violence. Some diaspora figures have openly called for armed resistance, framed violence as inevitable or necessary, and portrayed escalation as the only serious or authentic path forward. In this framing, restraint is equated with weakness, and nonviolent protest is dismissed as futile.

This escalation often functions less as a reflection of realities on the ground than as a narrative strategy aimed at sustaining momentum, attracting international attention, and pressuring foreign governments to intervene. Calls for armed protest are circulated online with little regard for feasibility, local capacity, or consequences. Casualties are frequently justified as a legitimate cost of “fighting for freedom,” with some voices going as far as to claim that even mass death—“even if a million people are killed”—would be worth it to bring down the regime.

Such rhetoric has severe consequences inside Iran. Escalation provides the state with justification for lethal force, allows security institutions to frame repression as counterterrorism, and dramatically increases casualty rates among protesters and bystanders alike. It also risks alienating broad segments of society who may support reform or protest but reject violent confrontation, thereby narrowing the movement’s social base.

Most critically, narrative escalation produces real-world bloodshed, borne by people who did not consent to such strategies and have no meaningful say in their articulation. Protesters on the ground absorb the costs of decisions made elsewhere—decisions shaped by distance, moral absolutism, and performative militancy rather than lived exposure to repression. In this sense, radicalising rhetoric does not merely misrepresent the movement; it actively reshapes it in ways that make survival, cohesion, and broad legitimacy increasingly difficult.

5. Legitimising the Regime’s “Foreign Plot” Narrative

One of the most damaging consequences of certain forms of diaspora activism is how easily they reinforce the regime’s central propaganda claim: that the uprising is not an indigenous social movement but a foreign-engineered plot. Calls made from abroad for U.S. or Israeli intervention—however driven by outrage or moral urgency—often amount to strategic self-harm for the protest movement itself.

Segments of the diaspora have openly advocated for sanctions escalation, airstrikes, regime decapitation, or even explicit coordination with foreign governments. While framed as tools of pressure, these demands supply the regime with precisely the evidence it needs to validate its long-standing narrative of external orchestration. The state does not need to invent foreign interference; it only needs to point to statements circulating openly in international media and on social platforms to portray the uprising as part of a geopolitical campaign rather than a domestic revolt.

Inside Iran, the effects of this framing are corrosive. By collapsing the distinction between popular dissent and foreign intervention, diaspora rhetoric undermines the domestic legitimacy of the protests. It makes protesters easier to criminalise as collaborators or security threats, provides justification for harsher repression, and shifts public debate away from governance failures toward questions of sovereignty and national survival. In a country marked by deep historical sensitivities to foreign intervention, this narrative can trigger a nationalist backlash, alienating undecided citizens and discouraging passive supporters from aligning with the movement.

At the elite level, the consequences are equally significant. Rather than fragmenting power, calls for external military action tend to unify regime elites, strengthen security institutions, and compress internal divisions. The uprising is reframed not as a political crisis but as an existential confrontation, allowing the state to mobilise loyalty, silence internal critics, and prioritise coercion over reform.

Diaspora advocacy for foreign intervention also frequently ignores the logic of war theory. It underestimates escalation dynamics, assumes controllable outcomes, and externalises the costs of confrontation to protesters who bear the consequences on the ground. Military intervention, far from accelerating political change, risks collapsing domestic support and converting a broad-based protest movement into a convenient foil for authoritarian consolidation.

In this sense, foreign intervention operates less as a solution than as a narrative trap. By internationalising the struggle in military terms, it transforms a domestic uprising into a geopolitical conflict—one in which the regime is often better positioned to survive, repress, and reassert control.

6. Disinformation, Exaggeration, and Credibility Loss

Another significant way in which parts of the diaspora have unintentionally harmed the protest movement is through the circulation of disinformation and exaggerated claims. Inflated casualty figures, unverified allegations, and dramatic but inaccurate reports have circulated widely across social media and exile platforms, often presented as established fact rather than provisional or contested information.

In the short term, this strategy can be effective. Shocking claims generate attention, drive engagement, and force international audiences to notice events unfolding in Iran. However, the long-term consequences are far more damaging. When figures are later questioned, revised, or contradicted by independent investigations, credibility begins to erode—not only for the individuals who spread the claims, but for the protest narrative as a whole.

This erosion of trust has tangible consequences. Journalists, human rights organisations, and policymakers become increasingly sceptical, slowing their responses and demanding higher evidentiary thresholds. Once doubt takes hold, even accurate reporting is scrutinised more aggressively or dismissed outright. Genuine abuses risk being reframed as exaggeration or propaganda, allowing the regime to deflect accountability.

In this sense, exaggeration undermines the very objectives it seeks to advance. Sustainable international advocacy depends on accuracy, consistency, and trust. When those foundations are weakened, the movement loses one of its most important sources of leverage: the ability to document repression in ways that compel credible, lasting action.

7. Silencing Dissent Within the Opposition

A further, often overlooked, consequence of diaspora-driven activism is the silencing of dissent within the opposition itself. As narratives harden and stakes are framed in existential terms, internal disagreement is increasingly treated not as legitimate debate but as betrayal. Diaspora discourse frequently polices ideological boundaries, narrowing the range of acceptable positions and voices.

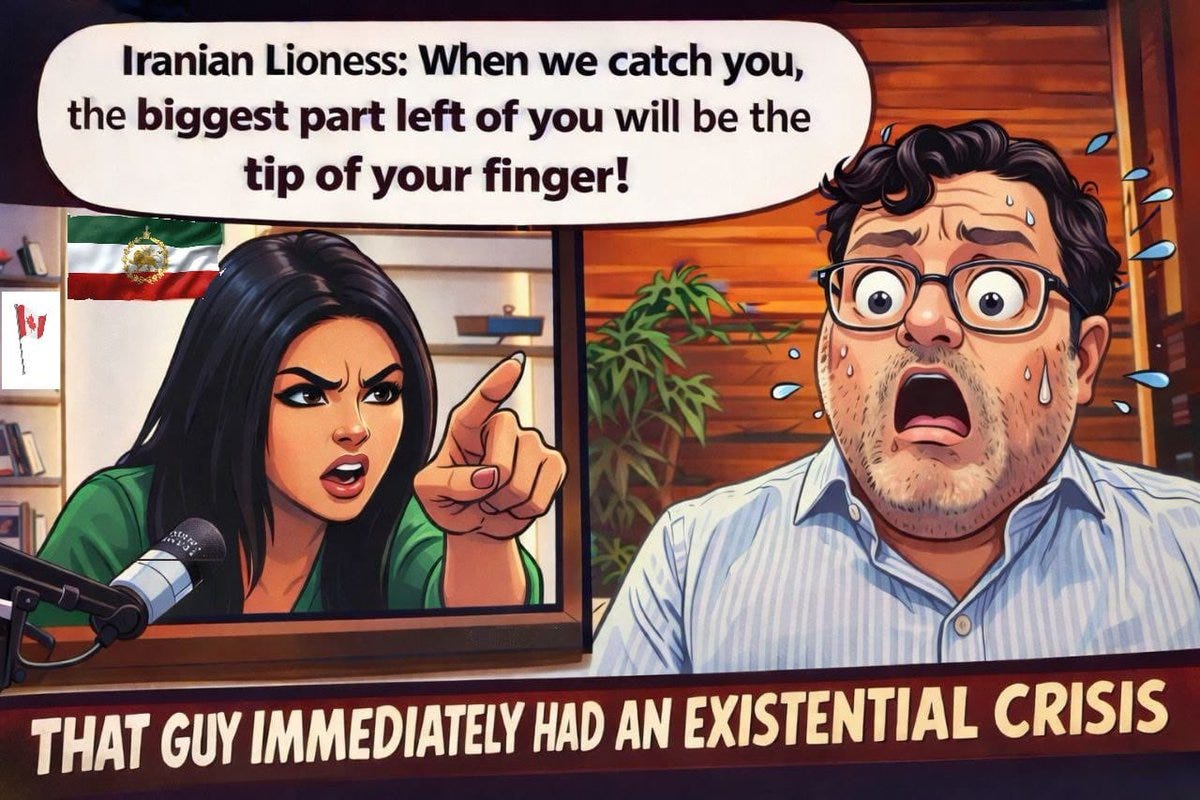

Moderate perspectives, calls for restraint, or critiques of escalation are often met with harassment and intimidation. Journalists, scholars, and analysts who question dominant framings have been publicly attacked, accused of collaboration, or branded as regime apologists. In some high-profile media appearances, this has gone further: opposition figures have openly threatened others on air—using violent metaphors and warnings of future retribution “after the protests”—to intimidate and silence dissenting voices.

This behaviour mirrors the very authoritarian practices the movement claims to oppose. By enforcing moral conformity and ideological gatekeeping, it narrows political imagination, discourages pluralism, and replaces persuasion with coercion. Instead of building a broad coalition capable of sustaining change, such tactics alienate undecided audiences and reinforce fears of vengeance or chaos in a post-regime scenario.

A movement that cannot tolerate internal disagreement struggles to build legitimacy. Suppressing debate does not strengthen unity; it weakens credibility and undermines the claim that the uprising represents a democratic alternative rather than a reversal of power with similar methods.

8. What Constructive Diaspora Engagement Could Look Like

Recognising the unintended harms of certain forms of diaspora activism does not mean disengagement. It means recalibration. Constructive diaspora engagement begins with a shift in orientation—from escalation to protection, and from spectacle to strategy. The goal should not be to outpace events on the ground with maximalist demands, but to support protesters in ways that reduce harm and preserve their agency.

One critical area is documentation. Diaspora networks can play a vital role in systematically collecting, verifying, and preserving evidence of human rights abuses in coordination with credible journalists, legal organisations, and international mechanisms. Accurate documentation strengthens long-term accountability far more effectively than sensational but unreliable claims.

Another key contribution lies in legal advocacy and humanitarian support. This includes supporting international legal efforts, advocating for due process protections, assisting political prisoners’ families, and facilitating humanitarian corridors for medical aid and emergency relief. These forms of engagement address immediate human needs without militarising the movement.

Digital security support is equally essential. Providing protesters and citizen journalists with tools, training, and resources to protect communications, evade surveillance, and safeguard identities can materially reduce risks on the ground. Unlike rhetorical escalation, such support directly enhances the resilience of grassroots activism.

Finally, constructive engagement requires respect for internal diversity, non-violent agency, and strategic patience. Protest movements are not monolithic; they contain multiple visions, tactics, and temporal horizons. Diaspora actors strengthen the movement when they amplify voices from inside Iran rather than substituting for them, when they accept disagreement as legitimate rather than treasonous, and when they recognise that endurance—not spectacle—is often the decisive factor in political change.

In short, effective solidarity does not seek to lead the movement from afar. It seeks to protect space for those inside the country to act, adapt, and decide their own future.

9. Conclusion: Solidarity Without Substitution

Protest movements often falter not only because of repression, but because their narratives are overtaken by external actors who claim to speak on their behalf. When voices far from the costs of struggle come to dominate how a movement is framed, the movement itself risks losing credibility, coherence, and strategic direction. Narrative dominance from outside can displace lived experience, flatten internal diversity, and turn complex social demands into tools of geopolitical or ideological contestation.

Supporting a struggle is fundamentally different from speaking over it. Solidarity strengthens movements when it protects space for those on the ground to act, decide, and adapt. It weakens them when it substitutes external certainty for local agency, replaces strategic patience with moral spectacle, or turns sacrifice into symbolism without consent.

The Iranian protest movement does not need saviours. It needs space, credibility, and time—space to organise under extreme pressure, credibility to sustain domestic and international support, and time to evolve without being forced into premature escalation. When diaspora activism replaces lived struggle with narrative dominance, it undermines the very movement it seeks to defend.

Reclaiming solidarity means returning it to its core function: amplification, not appropriation. It means listening before speaking, supporting without commandeering, and ensuring that the voices most at risk remain at the centre of the story being told.

Glad to read an assessment of these difficult matters that is moderate, attentive, and focussed on the long term.