Washington Has Lost Patience with Iraq’s Political Class

Why the U.S. Is Done With Iraq’s Old Guard—After Nouri al-Maliki’s Nomination and Trump’s Public Rejection?

Following intense internal negotiations, Iraq’s Coordination Framework—the largest parliamentary bloc, bringing together almost all Shiite political parties—announced its nomination of Nouri al-Maliki for the prime ministership. The move immediately reignited long-standing tensions around Iraq’s political direction, its relationship with Iran, and its standing in Washington.

Well before the nomination, U.S. officials had signalled—both publicly and through diplomatic channels—that Washington would not support figures perceived as closely aligned with Tehran, not only in the prime minister’s office but across the entire cabinet. The message was clear: the problem, in Washington’s view, is no longer limited to individual appointments but extends to the political ecosystem that sustains them.

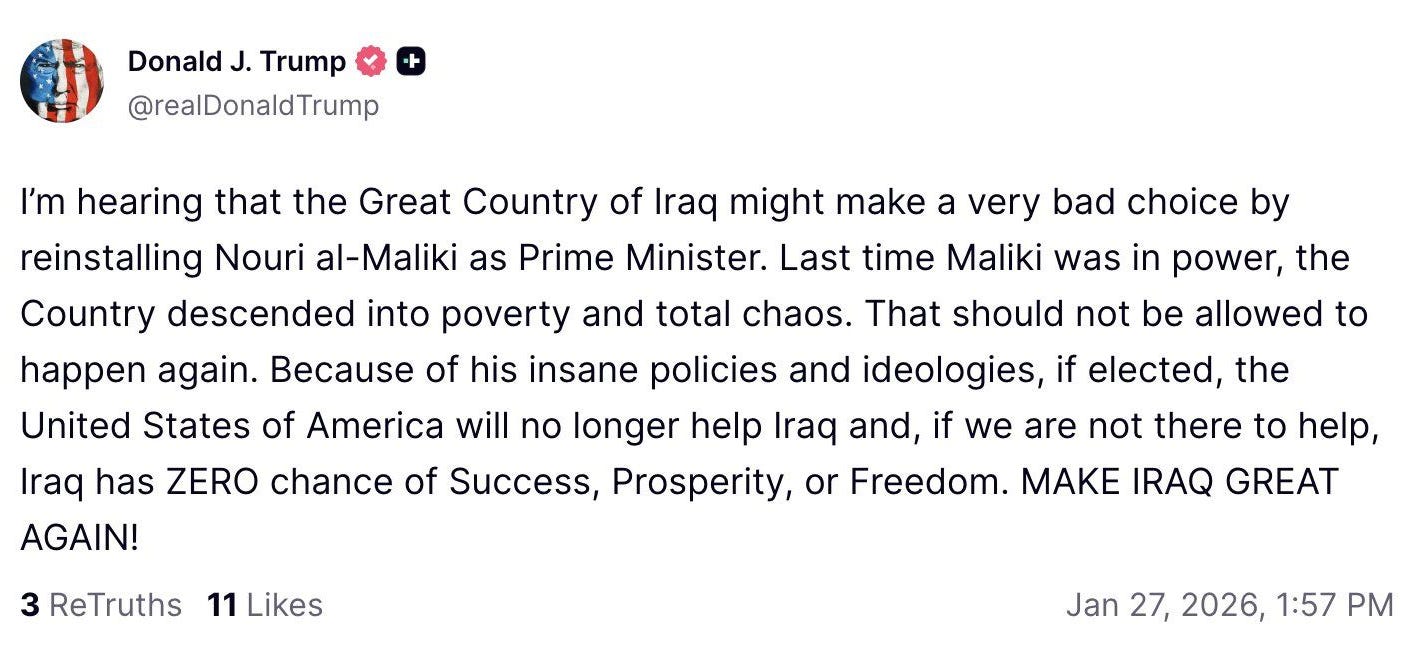

Donald Trump’s response removed any remaining ambiguity. Rejecting the nomination directly and publicly, he made clear that the United States would not assist Iraq under a government led by figures associated with the old order. This was not casual commentary or impulsive rhetoric. It was a strategic signal.

To Baghdad, the message was that continuity would no longer be rewarded with engagement or support. To Tehran, it signalled that Iraq is now being treated as a critical front in the broader effort to dismantle Iran’s regional influence. And to Washington’s regional partners, it underscored a shift in U.S. posture: patience with Iraq’s political recycling has run out, and ambiguity is no longer acceptable.

In this sense, Trump’s reaction was not merely a rejection of one nominee. It was a declaration that the rules governing U.S.–Iraq relations have changed—and that Iraq’s next political choices will be interpreted not as domestic compromises, but as strategic alignments.

Never Trust a Broken Sword

Washington’s rejection of Iraq’s political recycling did not emerge overnight. It is the product of accumulated lessons from two decades of failed experiments—experiments in which the United States repeatedly invested in leaders who promised alignment, reform, and distance from Iran, only to deliver dependency, ambiguity, and strategic double-dealing.

At the core of this disillusionment is a simple conclusion: Washington no longer believes Iraq’s old political class can produce a reliable partner capable of maintaining meaningful distance from Iran. Successive prime ministers presented themselves to the United States as reformers willing to curb Iran-backed militias, strengthen state institutions, and rebalance Iraq’s foreign policy. In practice, all previous PMs played a different game.

The pattern was consistent even though the tactics were diferent. Publicly and diplomatically, Iraqi leaders reassured Washington that they were committed to U.S. demands—containing militias, asserting state authority, and limiting Iranian influence. Privately and structurally, they treated Iran as the natural, long-term ally: geographically entrenched, ideologically aligned, and indispensable for regime survival. The United States, by contrast, was often viewed as a temporary power—dangerous if provoked, useful if appeased, but ultimately something to be managed rather than partnered with.

This duality was not abstract. During my service in Iraq, I witnessed senior Iraqi officials openly claiming to stand with Washington while simultaneously sending loyalty messages to Iran’s Supreme Leader, coordinating with Quds Force commanders such as Qassem Soleimani and later Ismail Qaani, and enabling Iran-aligned militias to entrench themselves across Iraq’s economy, security apparatus, and political system. These were not isolated incidents or rogue behaviours; they were features of a political culture built on hedging, duplication, and strategic ambiguity.

For years, the United States tolerated this contradiction in the name of stability. That tolerance has now evaporated. In Washington’s current calculus, Iraq’s political class resembles a broken sword—wielded repeatedly, promised reliability, but failing at the decisive moment. Trust has been exhausted not by one leader, but by a system that perfected the art of telling Washington what it wanted to hear while delivering Tehran what it needed.

The message today is blunt: the old game no longer works. The United States is no longer buying assurances, intermediaries, or performative alignment. In its view, Iraq’s traditional political elite has proven structurally incapable—or unwilling—to break from Iran. And a broken sword, once recognised as such, is no longer carried into battle.

No Grey Zone Anymore

From Washington’s perspective, Iraq is no longer a state that can balance comfortably between Iran and the United States. The era of strategic ambiguity—of hedging, dual messaging, and calibrated neutrality—has ended. Alignment is now viewed as binary.

For years, U.S. policy toward Iraq rested on engagement despite frustration. Washington accepted imperfect partners, tolerated delays, and overlooked contradictions in the hope that gradual reform, economic support, and security cooperation would pull Iraq closer to the Western orbit over time. That approach assumed that Iraq’s political system, even if slow and compromised, was ultimately capable of recalibrating itself.

That assumption has collapsed. Repeated compromises, recycled leadership, and unfulfilled promises have exhausted U.S. patience. Each political cycle reproduced the same figures, the same power-sharing logic, and the same dependence on Iran-aligned actors. Engagement, in Washington’s eyes, no longer produced leverage—it produced stagnation.

The post–7 October regional escalation accelerated this shift. What began as a campaign to dismantle Iran’s regional network has progressively moved closer to Iran’s core spheres of influence. Hezbollah, Hamas, and other fronts were weakened. Syria was reshaped. And now the logic has reached Iraq. In this context, Iraq is no longer treated as a special case or a fragile exception. It is being folded into a broader strategy aimed at severing Iran’s remaining channels of influence.

Under these conditions, compromise is no longer tolerated. The message from Washington is stark: Iraq must choose. Full alignment with the United States and its regional framework comes with political and economic support, security cooperation, and reintegration. Alignment with Iran, by contrast, carries clear consequences—withdrawal of support, isolation, and pressure that will no longer be softened by appeals to stability or sovereignty.

The grey zone that once allowed Iraq to maneuver has narrowed to the point of disappearance. What Washington sees today is not a country balancing between powers, but a decision deferred for too long. And in the current strategic climate, deferral is not a choice for Washington.

So Who Does Trump Actually Want?

The signals coming from Washington leave little room for interpretation. Through Trump’s own statements, as well as messaging delivered by his envoy to Iraq, Mark Savaya, and regional figures such as Tom Barrack, the United States has made clear that it is no longer negotiating personalities—it is setting conditions. What Washington wants is not a familiar name or a recycled figure from Iraq’s political class, but a fundamentally different profile of leadership.

At the core of these demands is a red line that did not previously exist in such absolute terms: zero participation of militias in government. This goes beyond cosmetic reforms or symbolic distancing. Washington is calling for the full dismantling of militia influence within the state, including the political and economic role of the Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMU). The militia-state hybrid that has defined post-2014 Iraq is now viewed not as a stabilising force, but as an obstacle to sovereignty and a conduit for Iranian power.

Equally explicit is the expectation of a clean break with Iran. No strategic coordination, no economic dependency, no back-channel bargaining. In Washington’s framing, Iraq cannot claim independence while remaining structurally tied to Tehran’s security and political architecture. Ambiguity is no longer acceptable.

The third pillar is regional realignment. The United States expects Iraq to abandon any posture of hostility toward Israel and to move—gradually but decisively—toward normalisation. This is not presented as a moral demand, but as a strategic requirement for reintegration into a U.S.-led regional order. Silence is no longer enough; neutrality itself is now interpreted as resistance.

Taken together, these conditions define the leadership profile Washington is seeking: a government with exclusive control over arms, independent from Iranian influence, aligned with U.S. regional priorities, and willing to break with the post-2003 political formula. Such a profile is not currently represented by most of Iraq’s dominant political forces.

The implications for Iraq’s political future are profound. Meeting these demands would require not just a change of leadership, but a transformation of the entire system that has governed Iraq for two decades. Failing to meet them, however, signals a different path—one in which Iraq is treated less as a partner to be stabilised and more as a problem to be contained.

Trump’s message is ultimately simple, if brutal: Washington is no longer prepared to work with half-measures or managed contradictions. Iraq can remain trapped in its old order, or attempt a painful redefinition of sovereignty. What it cannot do anymore is pretend that both paths are still open.

What Can Iraqi Politicians—Particularly Shiite Leaders—Do Now?

The reaction inside Baghdad was immediate. Following Trump’s rejection, the Coordination Framework convened an emergency meeting to reassess its options. The move itself underscored how seriously Washington’s message was taken—not as commentary, but as a veto with real consequences.

Within this context, the dynamics around Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani deserve close attention. Sudani, who had been competing with Maliki, ultimately withdrew from the race, apparently calculating—correctly—that Maliki’s nomination would trigger U.S. rejection. Yet this tactical manoeuvre does not translate into strategic advantage. Sudani’s own record places him firmly in the category Washington is moving away from: a leader positioned in the middle, managing contradictions rather than resolving them.

During Sudani’s tenure, Iran-aligned militias intensified hostile actions against Israel, and Iraq deepened strategic economic ties with Tehran, including agreements such as the Shalamcheh–Basra railway project. From Washington’s perspective, this reinforced the view that “centrist” governance has functioned less as balance and more as cover for continuity. Trump’s current posture leaves little room for this kind of political ambiguity.

The Coordination Framework now faces a defining choice: does it intend to lead Iraq into a new strategic phase, or merely manage the remnants of the previous one? The answer to that question will determine not only the next prime minister, but Iraq’s position in a rapidly hardening regional order.

The next government will not be a traditional “services government” focused on electricity, salaries, and short-term stability. It will be tasked with navigating a far more complex environment—economic pressure, regional realignment, and direct international scrutiny. Baghdad needs a prime minister capable of strategic negotiation, crisis management, and absorbing geopolitical friction, not simply defusing it.

Trump’s message, therefore, goes far beyond vetoing a single candidate. Maliki’s nomination—secured with the explicit blessing of Ali Akbar Velayati, senior adviser to Iran’s Supreme Leader—symbolised precisely the political continuity Washington now rejects. The signal from Washington is not for substitution within the same framework, but for structural change.

For Shiite political forces in particular, the moment is stark. Persisting with familiar figures and familiar tactics risks pushing Iraq into isolation at a time when regional margins for error are shrinking. Adapting, by contrast, would require confronting internal power structures that have defined post-2003 politics. The decision they make now will shape not just the next government, but whether Iraq is treated as a strategic actor—or as collateral—in the unfolding regional contest.