Understanding Trump’s Iran Strategy Through the Lens of War Theory

U.S. policy toward Iran has never followed a straight line. Over nearly five decades of confrontation since the 1979 revolution, Washington has oscillated between containment, selective military strikes, sanctions and inducements, reluctant coexistence, and periodic flirtation with outright regime change. Each phase reflected a different attempt to manage the same dilemma: how to deal with a revolutionary state that challenges U.S. power without triggering a catastrophic regional war.

Against this backdrop, Donald Trump’s rhetoric often appears contradictory. At times, he speaks in the language of regime change, echoing the most confrontational moments of U.S.–Iran relations. At other moments, he signals openness to negotiations that would leave the Islamic Republic intact. To many observers, this fluctuation looks like confusion or improvisation. But when viewed through the lens of modern war theory, it looks far more deliberate.

Trump’s apparent restraint is not the product of indecision; it is the result of strategic calculation. Iran is not just another adversary. It is a deeply embedded system with multiple layers of military, political, and economic entanglements, not to mention broad regional consequences, that make it exceptionally difficult to strike - unless in a limited calculated right-time-moment level like the strike on Fordo Nuclear facility during the 12 days war - without triggering wide and unpredictable escalation. In war-theory terms, Iran is not a conventional kind of war: one that cannot be easily limited, neatly controlled, won at acceptable cost, or even withdrawn from it at any time.

Escalation Theory: Why Iran Could Be a Trap

Cold War strategist Herman Kahn described military conflict as an escalation ladder—a sequence of steps in which each move increases the risk, scope, and cost of confrontation. The central danger lies not in the first step itself, but in the difficulty of controlling how far up the ladder a conflict will climb once it begins.

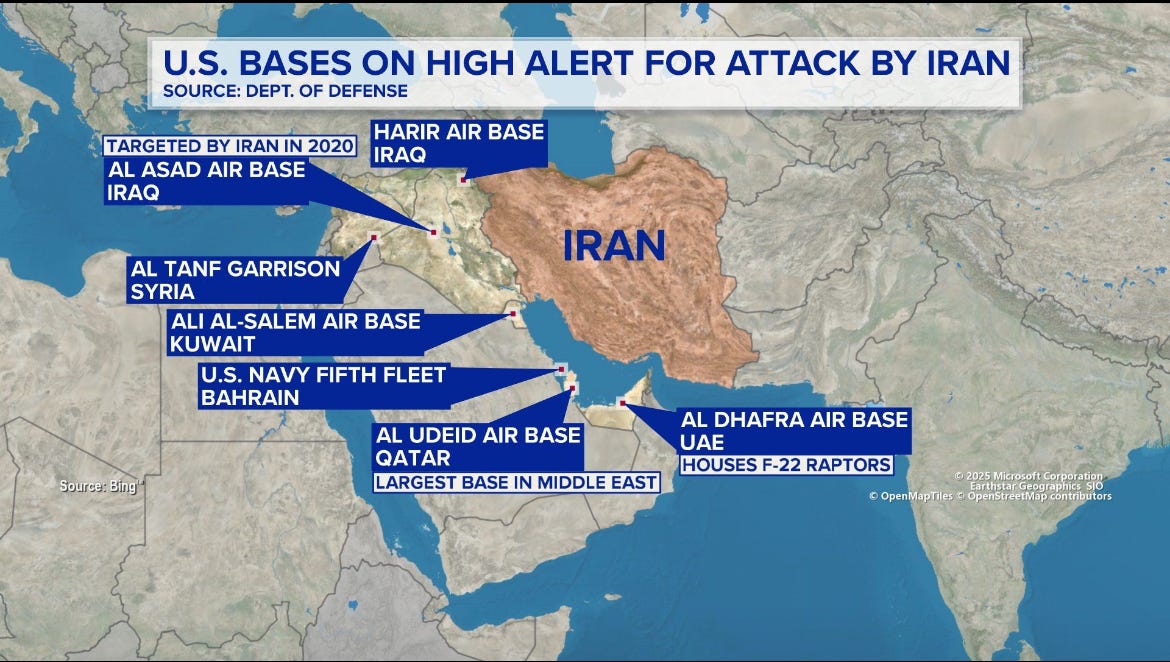

Iran’s escalation ladder is long and complex. Iran cannot be struck in isolation. Military action would immediately implicate a wider web of actors and interests, including regional militias, oil markets, and the strategic concerns of major powers such as Russia and China. This interconnectedness sharply limits the ability to control escalation. Any confrontation affects Israel’s security, the stability of the Gulf, and the safety of global shipping routes.

Any confrontation should not get to the level that pushes the regime toward a suicidal choice, to retaliate without calculation.

In war-theory terms, Iran represents an “un-limitable” conflict—one that cannot be neatly contained or easily calibrated if it does not occur in a calculated and limited level and at the right time. Trump’s caution reflects this reality. He does not avoid war as such; rather, he avoids wars that cannot remain small. That distinction goes a long way toward explaining the logic behind his Iran policy. He’s looking for the best option and the right moment to avoid heavy consequences.

The Logic of Limited War

Modern warfare is not always about conquest, occupation, or regime change. Limited war pursues narrower objectives: symbolic dominance, deterrence, reputational signaling, and psychological pressure rather than territorial control or political engineering. Its purpose is not to defeat an adversary outright, but to shape its behavior at an acceptable cost.

Trump’s approach to Iran fits squarely within this tradition. His policy operates through what can best be described as coercion without war—the use of pressure and threat to influence outcomes while deliberately stopping short of full military confrontation.

Clausewitz famously observed that:

“War is the continuation of politics by other means.”

Trump appears to take this principle seriously. His threats toward Iran function primarily as political instruments rather than military ones. Pressure is applied through public warnings, shifting deadlines, sanctions, cyber operations, diplomatic isolation, and the constant suggestion that force remains an option, reinforced by the possibility of limited strikes. The objective is to compel behavioral change without crossing the threshold into open war.

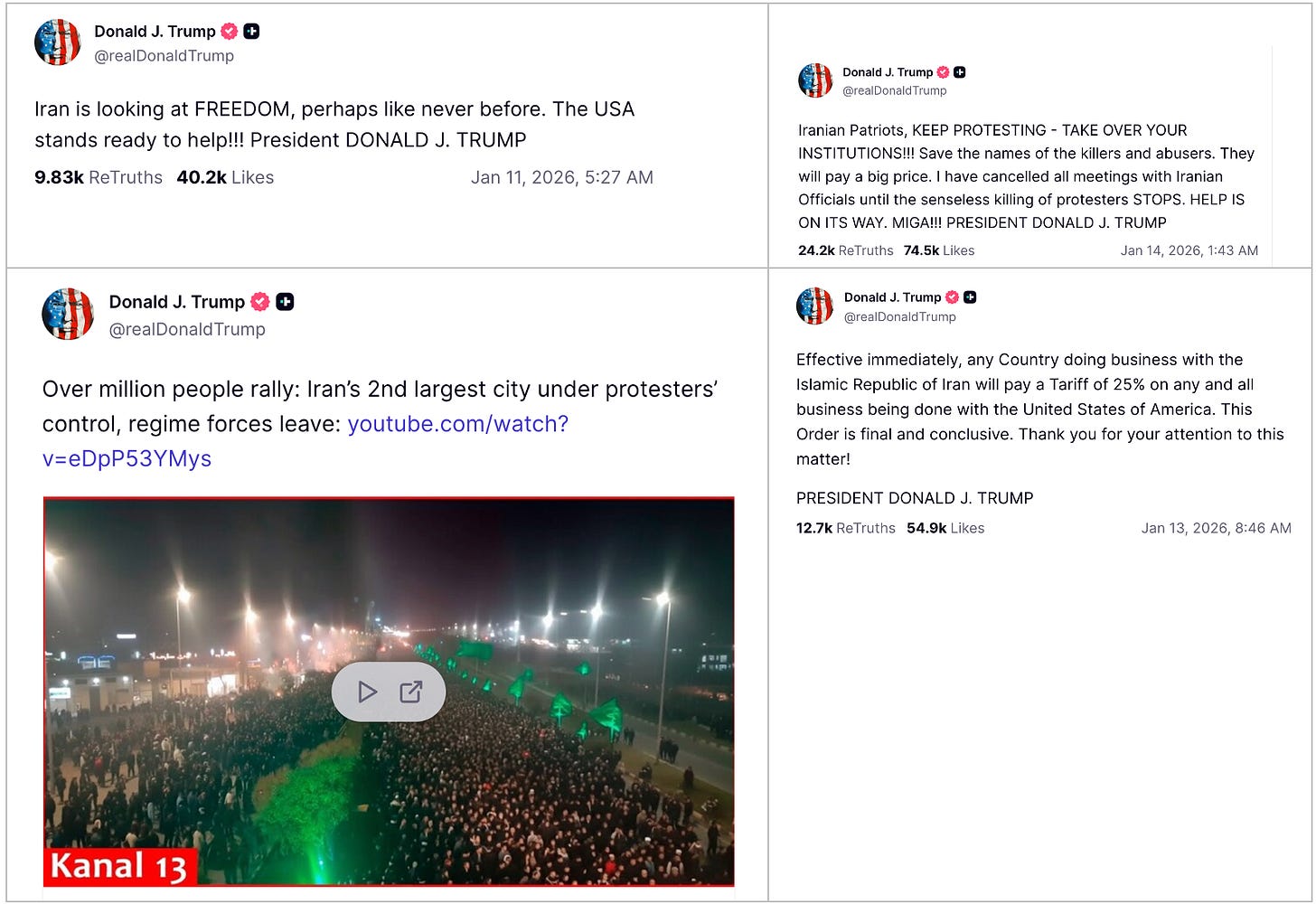

The eruption of protests inside Iran creates a particularly advantageous moment for this strategy. Trump can signal support for the Iranian public and increase pressure on the regime without triggering a regional crisis. A direct military strike, by contrast, would fundamentally alter the political logic. It would introduce a dynamic of escalation that Washington could no longer fully control.

In Clausewitzian terms, once bombs fall, politics ceases to steer events—and the conflict begins to move according to its own momentum.

Coercion VS Force

Strategist Thomas Schelling drew a foundational distinction between coercion and force that helps clarify the difference between Donald Trump’s strategic approach and that of neoconservatives such as George W. Bush.

In Schelling’s framework, coercion seeks to change an adversary’s behavior by threatening future pain or costs, while force aims to physically overpower or destroy an opponent. Coercion operates through what Schelling described as the “power to hurt,” shaping adversary decisions without necessarily resorting to full-scale violence. It includes deterrence (preventing an action) and compellence (inducing a change in action), both of which leave the ultimate choice with the opponent, albeit under pressure. Actual combat, by contrast, bypasses the adversary’s choice altogether, using violence to achieve an outcome.

Historically, neoconservative doctrine—most prominently under President George W. Bush—placed greater emphasis on the use of force to achieve political ends, particularly when peaceful change was deemed unlikely or undesirable. The 2003 invasion of Iraq, justified through a mix of security and hegemonic reasoning, reflects a willingness to convert coercive diplomacy into full military action when political goals could not otherwise be enforced.

By contrast, Trump’s Iran policy fits much more squarely into the realm of coercion. His repeated threats and public warnings—framed as conditional on Iranian actions, such as violence against protesters or continued nuclear development—function primarily as political instruments. They are designed to weaken regime legitimacy, raise internal costs, intimidate elites, and signal vulnerability without crossing the threshold into sustained warfare. This is coercion in its essence: influencing behavior through the threat or limited use of power rather than decisive military victory.

That is not to say Trump never uses force. In 2025, the United States participated in military strikes against Iranian nuclear facilities, targeting sites such as Fordow and Natanz in a limited operation alongside Israeli forces. And in early 2026, U.S. forces carried out an operation resulting in the capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, an action that drew significant international attention and legal debate.

Even these uses of force, however, were narrow and calculated rather than open-ended wars. The strike on nuclear facilities focused on specific targets tied to proliferation concerns, not regime overthrow. The Venezuelan operation, while dramatizing U.S. power, was framed in terms of law enforcement and regional stability rather than occupation, long-term combat and regime change.

The difference is significant. Under neoconservative models, once coercive diplomacy failed to achieve desired compliance, force would be the instrument of last resort—often with wide strategic aims and long commitments. Under Trump, force remains a supplement to coercion rather than its replacement. It is employed selectively, with limited scope and clear, bounded objectives.

Whether Trump will remain within this coercive equilibrium or escalate further remains uncertain. But the broader pattern of his foreign engagement suggests hesitation to gamble heavily on large-scale military force, especially when compared with neoconservative precedents. His strategy privileges coercive pressure and limited action—measured instruments designed to influence behavior without triggering uncontrollable escalation.

Bottom Line

Trump is not waiting because he is uncertain. He is waiting because, in strategic terms, Iran is already bleeding politically. War theory offers a simple lesson: when an adversary is eroding from within, external force can be counterproductive. Military intervention risks stabilizing what internal pressure is already weakening. In such moments, restraint is not passivity—it is strategy.

This logic explains why Trump has neither moved decisively toward negotiations with the Iranian regime nor launched a large-scale military response. Negotiations would relieve pressure on the system, while a major strike would risk unifying elites and legitimizing repression. Instead, Trump appears to be betting on maximum pressure, the continuation of domestic unrest, and the cumulative political cost imposed on the regime over time.

That does not mean force is entirely off the table. Trump’s pattern suggests that, if used, military action would be limited, highly selective, and carefully calibrated—designed to impose costs while minimizing the risk of escalation. Such strikes would aim to constrain Iran’s ability to retaliate widely and to avoid triggering a broader regional conflict.

This helps explain the apparent gap between rhetoric and action. While Trump warned that severe repression of protesters would trigger consequences, he has so far relied on alternative instruments: tightening economic pressure, targeting third parties that sustain Iran economically, and publicly encouraging protesters while signaling that external pressure would continue. These measures preserve coercive leverage without crossing the threshold into open war.

If force were to be used, it would likely be framed in political rather than purely military terms—targeting symbols or institutions associated with repression rather than pursuing sweeping battlefield objectives. Even then, the expectation would be a controlled exchange, in which Iranian retaliation remains limited and largely symbolic, allowing both sides to signal resolve without losing control of escalation.

In this framework, Trump’s strategy is not about decisive victory or rapid regime change. It is about managing pressure, prolonging internal strain, and keeping military options constrained. Whether this balance can be sustained remains uncertain, but the underlying logic is consistent: avoid large gambles, keep conflicts small, and let political erosion do the heavier work.