Seventy-Five Years On: Why There Is Still No Palestinian State

After 75 years of conflict, the Palestinians have still not been able to establish their own state. While the creation of both Israel and Palestine was proposed by the United Nations at the same time, only one side succeeded in forming its state. Each blames the other for the failure to establish a Palestinian state.

Israelis argue that Palestinians did not fully engage in the peace process and therefore missed their opportunity to form a state. Palestinians, on the other hand, accuse Israel of placing obstacles in their path and preventing them from doing so. So, what exactly happened—and what is the situation today?

Brief Conflict Background

In 1914, the Ottoman Empire entered World War I on the side of Germany. By 1918, the empire was defeated and signed the Armistice of Mudros, losing vast territories and paving the way for its full dissolution. Britain and France, the victors of the war, divided the Levant and Iraq between themselves, establishing mandates over these areas. Britain formed the mandates of Iraq and Palestine, while France took Syria and Lebanon.

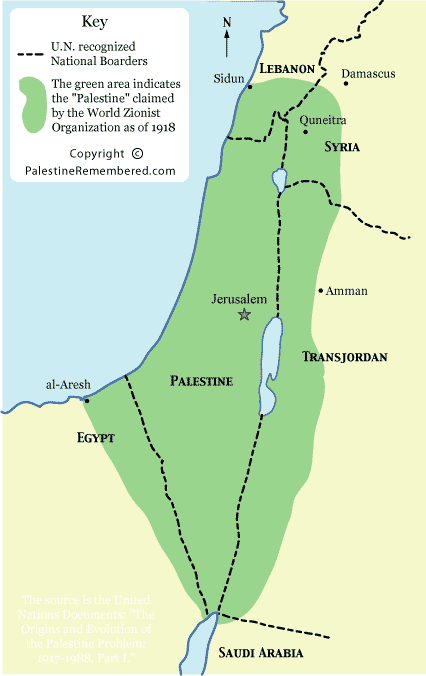

In 1947, the United Nations proposed the UN Partition Plan, recommending the creation of two independent but economically linked states—one Arab and one Jewish—along with an extraterritorial “Special International Regime” for Jerusalem and its surroundings. The plan allocated 42.88% of the territory to the Arab state, 56.47% to the Jewish state, and the remaining 0.65%—including Jerusalem and Bethlehem—would become an international zone.

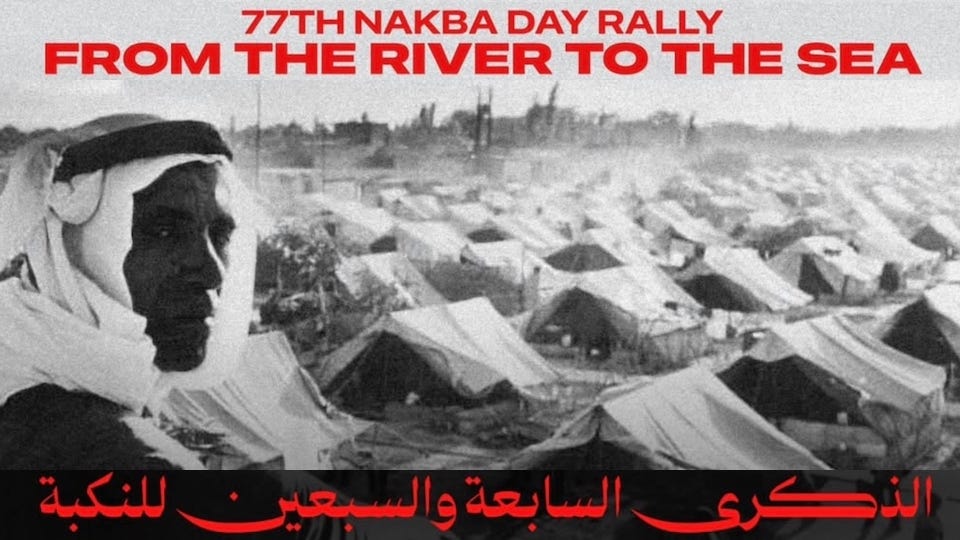

The British Mandate in Palestine officially ended on May 15, 1948. Jewish residents of Palestine, many of whom had migrated from various European countries, immediately declared the establishment of the State of Israel. This triggered a war between Jews and Arabs, leading to the displacement and dispossession of about 700,000 Palestinians—an event Palestinians refer to as the Nakba, meaning “catastrophe” in Arabic.

During the Nakba, Zionist forces launched an operation known as Plan Dalet, capturing cities, villages, and territories in preparation for establishing a Jewish state. On May 14, 1948, just before the expiration of the British Mandate, Zionist leaders announced the Israeli Declaration of Independence. The following morning, Egypt, Jordan, Syria, and expeditionary forces from Iraq entered Palestine, seizing Arab areas and attacking Israeli forces and settlements.

The fighting formally ended with the 1949 Armistice Agreements, which established the Green Line. As a result, Israel controlled all the territory allocated to it under the UN plan, plus nearly 60% of the land originally proposed for the Arab state.

Arab states attempted to reverse these losses in the wars of 1967 and 1973 but were defeated both times. By 1973, Israel not only held additional Palestinian land but also territories taken from Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan—while controlling all of Jerusalem and the majority of Arab territory.

The Peace Process

Since the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948, the question of Palestinian statehood has been at the center of every attempt at peace in the Middle East. Yet, despite decades of negotiations, international mediation, and high-profile summits, the envisioned Palestinian state remains unrealized.

The earliest serious proposal came in the aftermath of the 1967 Six-Day War, when UN Security Council Resolution 242 called for Israel to withdraw from territories occupied during the conflict in exchange for peace with its neighbors. The resolution also affirmed “the right of every state in the area to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries,” but it made no explicit provision for Palestinian sovereignty, leaving the issue unresolved.

The first formal recognition of Palestinian political representation came in 1974, when the Arab League declared the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people. This set the stage for the 1991 Madrid Conference and, more significantly, the 1993 Oslo Accords, where Israel and the PLO recognized each other and agreed to a framework for Palestinian self-rule in parts of the West Bank and Gaza. The accords envisioned a five-year transitional period leading to final status negotiations, including borders, refugees, security, and the future of Jerusalem.

However, the promise of Oslo faltered. Disputes over settlements, violence from both sides, and deep mistrust stalled the process. By the time of the Camp David Summit in 2000, the two sides remained far apart on core issues, especially Jerusalem and the right of return for Palestinian refugees. The summit’s collapse was followed by the outbreak of the Second Intifada, which further eroded trust and hardened positions.

Subsequent initiatives—such as the 2003 U.S.-backed “Roadmap for Peace,” the 2007 Annapolis Conference, and later talks brokered by U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry in 2013–2014—produced frameworks and proposals but no lasting agreement. The expansion of Israeli settlements in the West Bank, political divisions between Fatah and Hamas, and shifting regional dynamics have made the prospects for Palestinian statehood even more remote.

Today, while much of the international community continues to affirm the two-state solution as the preferred outcome, the gap between political rhetoric and realities on the ground has never been wider. Palestinians remain without a state, living under a mix of limited self-rule, occupation, and blockade, while Israel’s political leadership has grown increasingly divided over whether a Palestinian state is even desirable.

Main Obstacles

Despite repeated diplomatic efforts, the creation of a viable, independent Palestinian state has been blocked by several entrenched obstacles. These are not just political disagreements, but structural and demographic realities that have made the two-state solution increasingly difficult to achieve.

1. Fragmentation of the West Bank through Settlements

Over the decades, Israel has established a network of settlements, outposts, and bypass roads throughout the West Bank. These settlements, many deep inside areas envisioned for a future Palestinian state, have carved the territory into disconnected enclaves. The resulting patchwork makes it nearly impossible to create a geographically contiguous Palestinian state. In some areas, settlement blocs dominate strategic high ground and water resources, further limiting Palestinian development. This physical fragmentation has turned what was once envisioned as a united territory into a series of isolated pockets.

2. Linking the West Bank and Gaza

The geographical separation of the West Bank and Gaza has long been recognized as a critical issue for Palestinian statehood. The 2003 “Roadmap for Peace” proposed a permanent safe passage or corridor between the two territories. However, such a link faces significant logistical and political challenges, including disagreements over security control, infrastructure, and sovereignty. Without a practical and secure connection, the concept of a single Palestinian state encompassing both territories remains largely theoretical.

3. The Right of Return for Displaced Palestinians

One of the most sensitive issues in negotiations is the demand that Palestinians displaced in 1948—and their descendants—be allowed to return to their homes. For Palestinians, this is seen as a core right and a matter of justice. For Israel, however, a large-scale return would significantly alter the demographic balance, potentially ending the Jewish majority within its borders. As a result, Israel has consistently rejected an unrestricted right of return, offering instead limited resettlement, financial compensation, or relocation to a future Palestinian state—proposals that Palestinians have largely deemed inadequate.

4. Limits on Sovereignty

Even in proposals where Israel has agreed in principle to the creation of a Palestinian state, it has often sought to impose limits on the level of sovereignty. These include restrictions on the Palestinian state’s ability to maintain an independent military, control its airspace, or manage its borders without Israeli oversight. While Israel frames these measures as necessary for security, Palestinians view them as incompatible with genuine independence. The tension between Israel’s security concerns and Palestinian aspirations for full sovereignty has repeatedly derailed negotiations.

Together, these four issues have formed a persistent barrier to Palestinian statehood. While they are often addressed in peace proposals, they remain unresolved, and each passing year further entrenches the status quo.

“Less than a State”

One of the recurring points of contention in the peace process is the scope of sovereignty Israel is willing to grant the Palestinians. On several occasions, prominent Israeli leaders have stated openly that their vision for a Palestinian entity falls short of full statehood.

Former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, for example, repeatedly emphasized that any Palestinian state would need to be “demilitarized” and subject to strict Israeli security controls, including oversight of airspace, border crossings, and possibly even electromagnetic frequencies. He argued that such limitations were essential to prevent the West Bank from becoming a base for attacks against Israel, as happened in Gaza after Israel’s 2005 withdrawal.

Other senior officials have gone further, avoiding the term “state” altogether and instead speaking of granting the Palestinians “autonomy” or “self-governance” in certain areas. In these models, Israel would retain security authority over major roads, the Jordan Valley, and large settlement blocs, leaving Palestinians with administrative control over scattered enclaves but without the full attributes of sovereignty recognized under international law.

From the Israeli perspective, this approach balances their security concerns with the need to address Palestinian aspirations. However, for Palestinians, such proposals are seen as an attempt to formalize a system of limited autonomy rather than genuine independence. Palestinian leaders argue that anything “less than a state” effectively cements the current fragmentation and occupation under a different name, making a viable and sovereign Palestine impossible.

This divergence in definitions—what Israel calls “state” versus what Palestinians and much of the international community consider a real state—has become one of the fundamental stumbling blocks in the peace process.

The Arab Peace Initiative

In 2002, during the Arab League Summit in Beirut, Saudi Arabia spearheaded a landmark proposal known as the Arab Peace Initiative (API). The plan represented a unified Arab offer to end decades of conflict and normalize relations with Israel in exchange for a comprehensive peace settlement based on internationally recognized parameters.

The core of the initiative was straightforward: if Israel agreed to withdraw from territories occupied in the 1967 Six-Day War—including the West Bank, Gaza Strip, East Jerusalem, and the Golan Heights—and accept the establishment of a sovereign Palestinian state along the pre-1967 borders (often referred to as the “1967 lines” or “Green Line”), then all 22 Arab League member states would:

• Recognize Israel as a legitimate state.

• Establish full diplomatic and economic relations, ending the Arab-Israeli state of war.

• Provide security guarantees to ensure Israel’s safety.

• Cooperate on regional stability, trade, and development.

The proposal also addressed the Palestinian refugee issue, suggesting a “just and agreed upon” solution in line with UN General Assembly Resolution 194, which Palestinians interpret as affirming the right of return, while leaving room for negotiation to address Israel’s demographic concerns.

The initiative was reaffirmed multiple times—in 2007 and again in 2017—demonstrating broad Arab consensus. However, Israel’s responses have been lukewarm. While some Israeli officials acknowledged the plan as a positive basis for discussion, successive governments rejected the precondition of full withdrawal to the 1967 borders, viewing them as indefensible and incompatible with Israel’s security needs.

For Palestinians, the Arab Peace Initiative was a rare moment of collective Arab backing that combined political recognition of Israel with robust guarantees for Palestinian statehood. For many in the Arab world, Israel’s reluctance to engage seriously with the proposal reinforced the perception that the obstacle to peace was not Arab unwillingness to coexist, but Israeli resistance to a viable Palestinian state on pre-1967 lines.

“Greater Israel” Vision

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has recently reignited the controversial concept of a “Greater Israel,” a vision that extends Israeli sovereignty over territories beyond its internationally recognized borders. This expansionist ideology has long been associated with certain factions within Israeli politics and has sparked significant regional and international concern.

In August 2025, Netanyahu publicly expressed his support for the idea of a Greater Israel, encompassing not only all of historic Palestine but also parts of neighbouring Arab countries, including Egypt and Jordan. He stated, “The right of the Jewish people to the land of Israel is eternal and indisputable… therefore, Judea and Samaria will not be handed to any foreign administration; between the Sea and the Jordan there will only be Israeli sovereignty.” This rhetoric aligns with the slogan “from the river to the sea,” which has been associated with maximalist territorial claims.

Netanyahu’s statements have elicited strong reactions from neighboring Arab countries and the broader international community. The endorsement of a Greater Israel by Netanyahu raises significant questions about the future of peace in the Middle East. The expansionist vision challenges the internationally supported two-state solution, which envisions an independent Palestinian state alongside Israel. Furthermore, it exacerbates tensions with neighboring Arab countries, potentially destabilizing an already volatile region.

As Netanyahu continues to advocate for this vision, the international community faces the challenge of addressing the implications of such expansionist policies on regional peace, security, and the prospects for a lasting resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Hamas as an Asset for Israel

Israel’s policies, particularly under Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, have at times actively or indirectly contributed to divisions within Palestinian society, complicating the prospects for a unified Palestinian state. Netanyahu and his allies have frequently framed Hamas not merely as a security threat but also as a political tool to weaken Palestinian unity. By maintaining a hardline stance toward the Palestinian Authority (PA) in the West Bank while tolerating—or at least not aggressively confronting—Hamas in Gaza, Israeli strategy has reinforced the schism between the two main Palestinian factions.

This division serves multiple strategic purposes for Israel. A fragmented Palestinian leadership reduces the likelihood of cohesive negotiations, undermines international pressure for concessions, and allows Israel to position itself as the sole reliable partner for peace in the West Bank. Critics argue that measures such as selective economic sanctions, differential security policies, and indirect engagement with Hamas have, intentionally or not, strengthened the group’s influence in Gaza, further weakening the PA’s ability to claim authority over a unified Palestinian polity.

Former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak has repeatedly criticized Netanyahu’s policies, observing that they inadvertently promote the perception that Hamas in Gaza is an asset while the PA in the West Bank is a liability—effectively reversing the logic of a unified state-building process for political purposes. This dynamic has created what Barak calls a “poison pill” for any political process, making the prospect of Palestinian statehood even more remote, particularly in the aftermath of the October 7 attacks and Israel’s subsequent military actions in Gaza.

Under Netanyahu, these strategies align with a broader vision in which Palestinian statehood is perceived as a threat to Israel’s security and ideological objectives. By exploiting internal Palestinian rivalries, the Israeli government has helped ensure that the structural conditions necessary for a viable, sovereign Palestinian state remain unrealized, effectively managing the conflict in a way that perpetuates division.

Conclusion: Competing Narratives

The failure to establish a Palestinian state has long been a source of mutual recrimination. Israelis and Palestinians present sharply divergent accounts of where the responsibility lies, each rooted in their historical experiences, security concerns, and political realities.

From the Israeli perspective, the absence of a Palestinian state is often attributed to repeated Palestinian rejection of compromise proposals—from the UN Partition Plan in 1947 to later negotiations at Camp David (2000) and Annapolis (2007). Many Israeli leaders argue that Palestinian factions, particularly Hamas, have undermined trust by refusing to recognize Israel’s right to exist, launching attacks on Israeli civilians, and maintaining maximalist positions on issues like the right of return for refugees. They also contend that deep divisions between the Palestinian Authority (PA) in the West Bank and Hamas in Gaza make it unclear who can credibly sign and implement a peace agreement.

From the Palestinian perspective, the responsibility lies with Israel’s entrenched policies of occupation and settlement expansion. Palestinians point to the fact that, even during peace talks, Israel has continued building settlements in the West Bank—fragmenting the land into disconnected enclaves that make a contiguous, viable state nearly impossible. They also highlight Israel’s control over borders, resources, and movement, which severely limits Palestinian self-determination. To many Palestinians, Israeli offers for statehood have been conditional, falling short of true sovereignty—more akin to an autonomy arrangement under Israeli oversight than an independent nation.

Given the current circumstances, the prospect of a two-state solution appears increasingly remote. Over decades, Israel’s consistent policies—particularly settlement expansion, territorial fragmentation, and limits on Palestinian sovereignty—have made the creation of a viable, contiguous Palestinian state nearly impossible. What was once a central vision for peace now faces realities on the ground that may have closed the door on it for good.