One ISIS, Different Treatments

How Geopolitics Rewrites Terrorism, Victims, and Accountability: The Syria Case

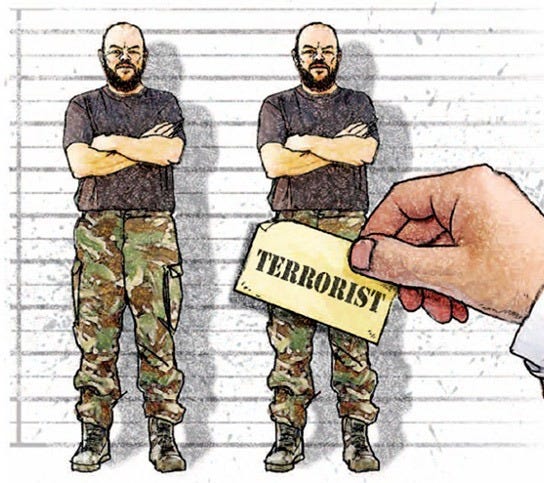

The label of “terrorism” has never been applied consistently. History shows that violent actors are often judged less by their methods than by their alignment—and that the same tactics can be celebrated, tolerated, or condemned depending on whom they target and whose interests they serve.

A familiar example is al-Qaeda. When its predecessors fought the Soviet Union in Afghanistan during the Cold War, they were widely framed as resistance or liberation forces. The same networks, when later active in Chechnya against Russia, continued to benefit from a degree of geopolitical ambiguity. Yet after 9/11—once their violence directly targeted the United States—those actors were unequivocally reclassified as terrorists, triggering a global war in their name. The violence itself had not fundamentally changed; its targets and strategic implications had.

A similar pattern is now visible in Syria. Jihadist groups that were once condemned as extremist threats are being rebranded after their incorporation into government-aligned forces. Their methods—executions, intimidation, collective punishment, and forced displacement—remain disturbingly familiar. What has changed is their political positioning. As they move closer to state power and align with actors favoured by influential international stakeholders, the language surrounding their violence shifts from outright condemnation to hesitation, justification, or strategic silence.

Violence is no longer judged primarily by what is done to civilians, but by who commits it—and who stands to benefit. When terrorism becomes a matter of alignment rather than action, accountability erodes, victims become negotiable, and the very meaning of counterterrorism is rewritten by geopolitics rather than principle.

The Problem of Syria’s New Military Forces

Moving beyond headlines reveals a far more troubling reality than the language of “security operations” or “state consolidation” suggests. The pattern of behaviour displayed by Syria’s new military forces over the past year—particularly in southern, western, and eastern Syria, where minority communities are concentrated—raises serious alarms. These forces are routinely described as government-aligned, but that label obscures who they actually are and how they operate. What is emerging instead is a pattern of ISIS-style violence carried out under state cover.

These units are not conventional national forces in any institutional sense. They are composed largely of former jihadist factions, rebranded militias, and foreign Salafi fighters who have been absorbed into the state’s security architecture without undergoing any meaningful ideological, organisational, or accountability-based transformation. What has changed is not their worldview or methods, but their political utility. Alignment with state authority has granted them legitimacy, protection, and international tolerance—without accountability.

The human cost has been severe and unevenly distributed along communal lines. According to Syrian human rights organisations and local monitoring groups:

• In southern Syria, particularly in predominantly Druze areas, hundreds of civilians have been killed over the past year during so-called security operations, including targeted assassinations and reprisals following local resistance.

• In western Syria, Alawite communities have faced waves of arrests, disappearances, and killings. Rights groups estimate that hundreds of Alawite civilians have been killed or disappeared since government-aligned forces reasserted control, often under the pretext of rooting out “regime remnants” or “security threats.”

• In eastern and northeastern Syria, Kurdish civilians have borne the brunt of the violence. Reports document hundreds of civilian deaths, mass displacement, and systematic intimidation as Kurdish-controlled areas were overrun. Entire villages have been emptied through raids, arbitrary detention, and property destruction.

Across these regions, the tactics are consistent: summary executions, forced displacement, and collective punishment aimed at breaking communal resistance rather than restoring order. Entire communities are treated as suspect, with violence deployed not to neutralise specific threats but to impose submission through fear.

Analytically, the violence bears unmistakable structural similarities to ISIS methods. The use of terror as a tool of governance, the targeting of communities based on identity, and the instrumentalisation of brutality to enforce control are all hallmarks of ISIS rule. The difference lies not in tactics, but in context. Where ISIS operated openly as an insurgent organisation, these forces act under the umbrella of state authority or state tolerance.

This distinction may matter politically, but it does not matter morally—or empirically. When identical methods are deployed—execution, displacement, intimidation—the reclassification of perpetrators does not alter the nature of the violence. What is unfolding in Syria today is not a deviation from extremist behaviour, but its institutionalisation under a new flag, shielded by geopolitical convenience rather than transformed by genuine reform.

One ISIS, Two Judgments

This is the conceptual core of the argument—and the most uncomfortable part of the story.

Between 2014 and 2019, the international response to ISIS violence in Syria and Iraq was unambiguous. Mass executions, ethnic cleansing, sexual enslavement, forced displacement, and rule through terror were universally condemned. The Yazidis and Kurds were recognised as victims of crimes against humanity. Emergency resolutions were passed, air campaigns launched, tribunals discussed, and humanitarian corridors opened. The moral language was clear because the perpetrator was clear: ISIS. Violence had a name, and accountability followed—at least rhetorically.

Fast forward to 2024–2026, and the picture becomes morally distorted. In southern, western, and eastern Syria, Druze, Alawite, and Kurdish communities have faced patterns of violence that are structurally familiar: summary executions, forced displacement, intimidation, and collective punishment. The methods resemble those once attributed to ISIS rule. The suffering, from the perspective of civilians on the ground, is no less real.

Yet the international reaction has changed.

Instead of condemnation, there is silence.

Instead of emergency language, there is hesitation.

Instead of accountability, there is “complexity.”

Why? Because the perpetrators are no longer framed as terrorists. They are now described as government-aligned forces, security actors, or partners in stabilisation. Their violence is reclassified—not denied, but contextualised, diluted, and politically managed. The same acts that once triggered airstrikes are now discussed as unfortunate excesses of state consolidation.

This is not a shift in moral standards; it is a shift in alliances.

The victims did not change.

The perpetrators did not change.

Only the alliances did.

And when alliances become the lens through which violence is judged, terrorism does not disappear. It is merely rebranded—absorbed into state structures, shielded by diplomatic necessity, and rendered selectively invisible. This is how extremist violence survives defeat: not by winning, but by being useful.

Why This Matters Beyond Syria

It is geopolitics over principles.

What is unfolding in eastern Syria cannot be understood as a local security matter. It reflects a broader geopolitical recalibration in which principles—human rights, minority protection, accountability—are increasingly subordinated to strategic convenience. The Kurdish question sits at the center of this shift as a clear example of shifting positions based on pourly geopolitical interests.

1. The New Syrian Government: Normalisation Over Accountability

The emerging Syrian leadership has sent clear signals that its priority is international rehabilitation, not internal reconciliation. Chief among these signals is a willingness to normalise relations with Israel and align more closely with Western security expectations. This positioning has dramatically altered how violence carried out by government-aligned forces is perceived abroad.

By presenting itself as a stabilising authority, committed to regional order and hostile to Iranian expansion, the new Syrian government has gained a degree of political immunity. Abuses committed in the process of consolidating control—particularly against Kurds, Druze and Allawites—are reframed as transitional excesses rather than structural crimes. In this equation, accountability becomes negotiable, so long as Damascus is moving in the “right” geopolitical direction.

2. Türkiye: Crushing Kurdish Autonomy at the Source

For Türkiye, Kurdish autonomy in Syria is an existential red line. Ankara views any form of Kurdish self-rule—especially one linked to PKK-affiliated structures—as a direct threat to its domestic stability. The fear is contagion: that Syrian Kurdish autonomy would embolden Kurdish political demands inside Türkiye.

This explains Ankara’s readiness to tolerate, and in some cases support, aggressive measures against Kurdish forces in Syria. From Türkiye’s perspective, dismantling Kurdish governance structures outweighs concerns about extremist violence, civilian harm, or the long-term risk of ISIS resurgence. Anti-Kurdish strategy takes precedence over counterterrorism consistency.

3. The United States: One Loyal Authority, Not Fragmented Partners

Washington’s position reflects a strategic fatigue born of years of fragmented alliances. After relying on Kurdish forces as tactical partners against ISIS, the U.S. now appears increasingly committed to a different objective: a single, controllable, and cooperative authority in Damascus.

From this standpoint, Kurdish autonomy is no longer an asset but a complication. It fragments sovereignty, complicates diplomacy, and risks entangling the U.S. in perpetual intra-Syrian conflict. The result is a quiet shift: pressure on Kurdish actors to integrate, disarm, or accept a diminished role in exchange for nominal protection—despite the clear risks this entails.

4. Iran: Should be Constrained

Iran remains a factor, but a weakened one. Historically, Tehran cultivated influence through PKK-linked networks and non-state actors across Syria and Iraq. Recent reports of Kurdish outreach to Hezbollah—however limited—have heightened U.S. and Israeli anxieties that Iran could rebuild regional leverage through alternative channels if Kurdish actors are marginalised.

This fear paradoxically reinforces pressure on the Kurds. Rather than being protected as former allies, they are treated as potential liabilities—spaces where Iranian influence might re-emerge. Iran’s role, therefore, is not dominant but catalytic: its shadow shapes decisions even where its direct power has receded.

5. Israel: From Tactical Ally to Strategic Silence

Israel has historically maintained quiet, tactical ties with Kurdish actors, viewing them as a counterweight to hostile regional forces. But that relationship was never strategic in the long-term sense. Today, Israel’s overriding priority is a weakened, predictable Syria that poses no military threat and signals openness to normalisation.

Positive messages from Syria’s new leadership—particularly under Ahmed al-Sharaa—have shifted Israel’s calculus. Strategic silence has replaced vocal concern. Past alliances with Kurdish forces are deprioritised in favour of a broader regional realignment that promises security, territorial dominance, and diplomatic breakthroughs.

The Broader Logic

Taken together, these positions reveal a stark hierarchy of values:

• The United States prioritises order over justice.

• Israel chooses silence over past alliances.

• Türkiye places anti-Kurdish objectives above ISIS risk.

• Iran probes for openings but operates under constraint.

The result is a system in which the conversation on human rights and terrorism have become inconvenient to everyone at once. This is not an accident of policy, but the outcome of a geopolitical consensus in which stability is defined narrowly, and accountability is conditional.

In such an environment, violence does not disappear. It is simply tolerated—so long as it serves the right alignment.

ISIS Risk for Iraq

Why Iraq Is Alarmed?

Beyond the immediate humanitarian and political consequences in Syria, recent developments have triggered deep anxiety in neighbouring Iraq—an anxiety rooted in bitter historical memory and hard intelligence assessments.

One of the most destabilising elements of the current phase has been the release of ISIS-affiliated individuals and families from al-Hawl camp without meaningful security vetting. Al-Hawl has long been recognised as a volatile incubator of radicalisation rather than a neutral humanitarian space. Its population includes thousands of women and children tied to ISIS networks, many of whom have maintained ideological commitment and informal organisational structures inside the camp. Releasing individuals from this environment without proper screening or deradicalisation mechanisms does not neutralise risk; it redistributes it.

Compounding this danger is the breakdown of detention control across parts of eastern Syria. Prison chaos, administrative collapse, and shifting chains of authority have weakened oversight of ISIS detainees. Facilities once guarded by Kurdish-led forces—under close international monitoring—are now subject to uncertain control arrangements. This creates gaps that militant networks are historically adept at exploiting.

Most alarming for Baghdad is the transfer of thousands of ISIS detainees from Syria to Iraq, facilitated with the US coordination. While framed as a burden-sharing or security-management measure, the move has reignited fears of repeating a catastrophic precedent. Iraq has lived through this scenario before.

The 2014 parallel looms large. Then, mass prison breaks in both Iraq and Syria, porous borders, and cross-border movement from Syria into Iraq enabled ISIS to regenerate with stunning speed. Fighters escaped detention, regrouped, crossed borders, and transformed from a weakened insurgency into a proto-state controlling vast territory. Iraqi institutions paid the price in blood, collapse, and long-term instability.

This historical trauma is now reinforced by current intelligence. Iraq’s intelligence chief, Hamid al-Shatri, has publicly warned that the number of ISIS fighters operating in Syria has increased tenfold within a single year. Such an assessment is not rhetorical—it reflects operational indicators, recruitment patterns, and movement across ungoverned or weakly governed spaces.

For Iraq, the danger is not abstract. It is immediate and structural. The release and transfer of ISIS-linked individuals risk recreating the precise conditions that allowed the group’s previous resurgence: fragmented authority, overstretched security forces, ideological continuity, and regional spillover. In this sense, what is unfolding in Syria is not only a Syrian crisis—it is a regional security gamble, with Iraq once again positioned on the front line.

In conclusion, what is unfolding in Syria illustrates a broader and deeply consequential shift in how violence is interpreted and managed in international politics. When acts that once triggered universal condemnation are reclassified or relativised because the perpetrators are now aligned with state authority or strategic partners, the definition of terrorism itself becomes unstable. This does not only undermine moral consistency; it weakens the very mechanisms intended to prevent the recurrence of mass violence.

Selective enforcement and strategic silence may appear to offer short-term order, but they obscure risks that accumulate over time. Communities that were once protected become exposed, extremist methods are normalised under new labels, and accountability is deferred rather than resolved. In such an environment, the problem is not that extremist violence disappears, but that it is absorbed, repackaged, and redeployed within new political arrangements.