Comic-Book Diplomacy: When the Joker Became Iran’s UN Ambassador

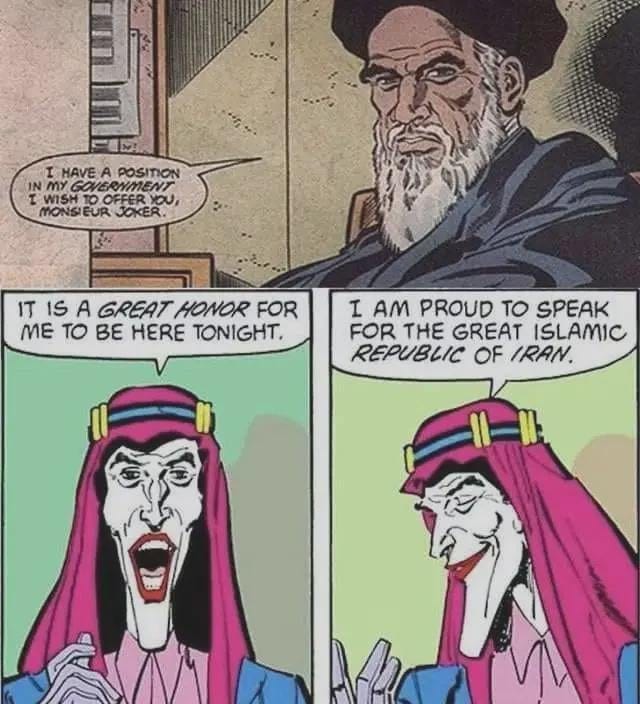

When DC Comics published A Death in the Family in 1988, one scene in particular shocked readers: the Joker was fictitiously appointed by Ayatollah Khomeini as Iran’s ambassador to the United Nations, granting him diplomatic immunity to evade Batman. The choice was deliberate. The Joker—one of popular culture’s most recognisable symbols of chaos, nihilism, and moral inversion—was used to satirise the absurdities, mistrust, and theatrical antagonism of late–Cold War geopolitics.

At the time, this was clearly fiction. But it was not accidental fiction. It was an early cultural experiment in turning diplomacy into spectacle—where power was expressed not through negotiation or law, but through shock, symbolism, and performative defiance. What appeared playful or grotesque on the surface carried a serious subtext about how threat and authority could be communicated beyond conventional diplomatic language.

This matters because it foreshadowed a deeper transformation that is now fully visible. Contemporary diplomacy increasingly relies less on formal statements, legal frameworks, or quiet signalling, and more on spectacle, cultural shorthand, and emotionally charged imagery. In this environment, symbols often speak louder than policy, and provocation travels faster than restraint. The question is no longer whether such references are appropriate or offensive, but what it means when states adopt the language of comic-book villains in arenas meant to manage conflict rather than perform it.

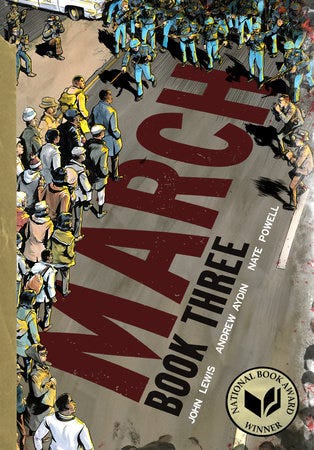

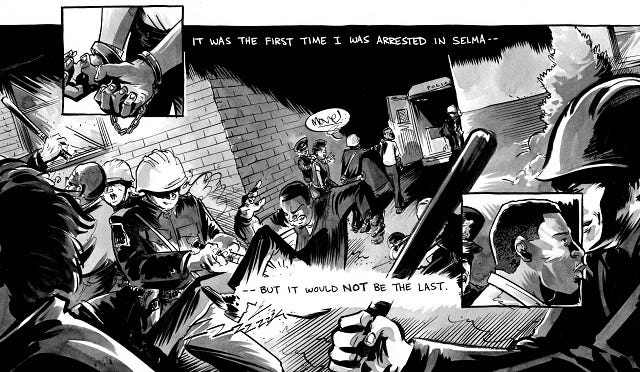

The irony is striking. The term “comic-book diplomacy” originally referred to something very different: the use of comics, graphic novels, and animation as tools of public diplomacy and cultural exchange. For decades, governments—most notably the United States—employed visual storytelling to promote dialogue, empathy, and social awareness abroad. U.S. embassies commissioned comics addressing human trafficking in Mexico, women’s empowerment in Kazakhstan, and trauma recovery in Georgia. During World War II and the Cold War, comic books served as ideological instruments, framing global struggles in accessible moral narratives. More recently, works such as Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi or March by John Lewis offered humanised, reflective accounts of identity, resistance, and political struggle—forms of cultural diplomacy aimed at understanding rather than intimidation.

Persépolis (2007): story of a childhood coinciding with regime change and war in Iran, Marjane Satrapi, WinshlussYet popular culture has always carried a darker mirror of international politics. In A Death in the Family, the Joker’s appointment as Iran’s UN ambassador was a grotesque exaggeration—a satirical commentary on diplomatic cynicism and the performative nature of hostility. What once felt absurd now feels unsettlingly familiar.

The 1988 Batman comic was not merely a joke; it was an early illustration of how geopolitics could be flattened into spectacle through popular culture. Today, that logic dominates international discourse through memes, virality, and narrative warfare. When states borrow from comic-book symbolism, they are no longer practicing cultural diplomacy designed to persuade or build legitimacy. They are engaging in performative psychological warfare—where symbolism replaces persuasion, defiance replaces dialogue, and spectacle displaces negotiation.

This is not only diplomacy slipping into humour, it is diplomacy slipping into theatre.

Meme Warfare

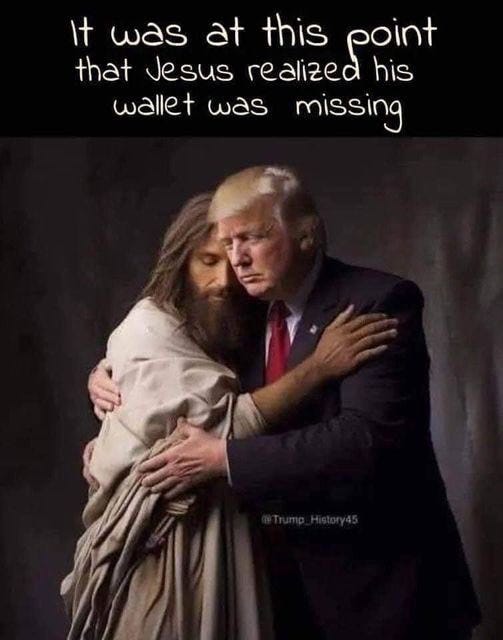

The return of religion to politics in the early twenty-first century has not only reshaped policy and ideology—it has also transformed the visual language of political communication. Nowhere is this clearer than in the rise of meme warfare, where religious figures, sacred narratives, and theological symbolism are repurposed into viral political imagery. What once belonged to sermons and scripture has migrated into timelines, feeds, and digital battlegrounds.

Religious memes function differently from conventional political messaging. They bypass policy debate and appeal directly to moral certainty, destiny, and divine legitimacy. By invoking sacred figures, leaders and movements present contemporary struggles not as contingent political conflicts, but as timeless battles between good and evil. In doing so, they collapse the distance between theology and statecraft.

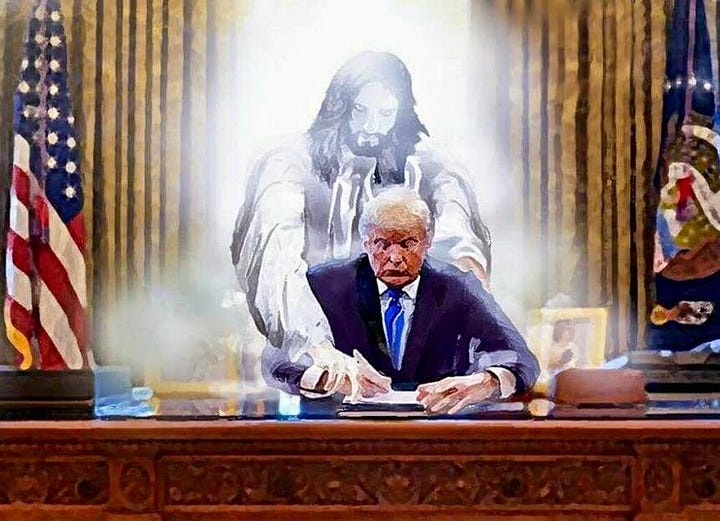

This phenomenon cuts across ideological lines. In the United States, religious symbolism has long been mobilised opportunistically in politics—most visibly in portrayals of Donald Trump as a messianic figure, or in Trump’s own selective invocation of Christianity to frame himself as a defender of faith, nation, and civilisational order. These images are not about theology; they are about authority, identity, and mobilisation. Religion becomes a prop, stripped of nuance and deployed for emotional resonance.

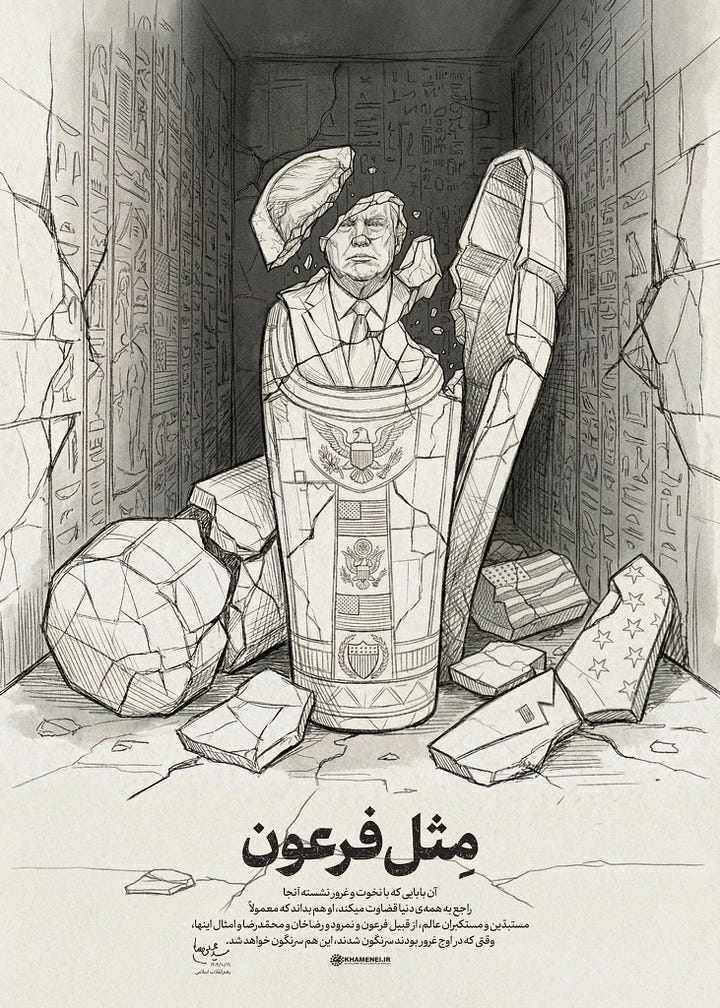

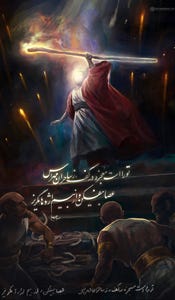

In Iran, the use of religious imagery is more overt and institutionalised. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has repeatedly shared visual content framing contemporary political struggles through Qur’anic and prophetic metaphors. Memes depicting Moses wielding his miraculous staff, implicitly linking Khamenei’s leadership to prophetic continuity, are designed to situate present-day confrontation within a sacred historical arc. Others portray Donald Trump as a fallen Pharaoh—a ruler brought low by divine justice—invoking the Exodus narrative to suggest inevitability, moral superiority, and eventual triumph.

These are not casual or humorous gestures. They are acts of theopolitical signalling. By drawing on shared religious memory, such imagery speaks to domestic audiences in a language of faith and destiny, while simultaneously projecting defiance to external adversaries. The message is not “we will win,” but “we are on the right side of history—and God.”

Meme warfare thus represents a fusion of digital culture and sacred symbolism. It thrives on ambiguity, virality, and emotional compression, allowing complex political claims to be reduced to instantly recognisable moral frames. In this environment, cartoons and memes become weapons—not because they persuade rationally, but because they sanctify power, delegitimise opponents, and transform politics into a theatre of cosmic struggle.

When religion enters meme warfare, politics no longer argues—it prophesies.

Sarcasm, Humiliation, and the Risk of War

Sarcasm, personal humiliation, and public insult have increasingly become tools of diplomacy—especially in the phase before negotiations begin. These are not random outbursts or undisciplined rhetoric. They are often deployed deliberately to weaken the other side psychologically, undermine its legitimacy, and improve bargaining position at the table.

President Donald Trump’s statements are a clear example. When he claimed, “I saved Khamenei’s life” implying that his location was known during the 12-day war and he stopped the attack, the message was not merely boastful. It was a calculated assertion of dominance: a reminder that restraint was a choice, not a limitation. When he followed this by calling Khamenei “sick man” and a “killer,” the intent was to delegitimise Iran’s leadership personally, not just politically.

Tehran responded in kind. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s references to Trump as a “clown” and a “criminal” were not aimed at persuasion or de-escalation. They were acts of symbolic resistance—designed to deny Trump moral authority and project defiance to domestic and regional audiences.

This exchange is more than political rhetoric. Each insult alters the strategic environment. Like financial markets reacting to central bank statements, the probability of war or negotiation fluctuates with every word. Public humiliation raises reputational stakes, narrows room for compromise, and locks leaders into positions from which retreat becomes politically costly.

History shows how dangerous this dynamic can be.

In 1914, European leaders wrapped a solvable crisis in rhetoric of honour, destiny, and inevitability. Diplomatic exits existed after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, but public commitments and escalating language turned mobilisation itself into a point of no return. War followed not because it was desired, but because rhetoric eliminated off-ramps.

In 2003, the Iraq War was preceded by moral absolutism: an “Axis of Evil,” “mushroom clouds,” and existential framing that transformed a containable regime into an urgent threat. Once humiliation and demonisation dominated discourse, backing down became politically impossible—even when inspections and alternatives were still viable.

In 1967, Arab leaders’ maximalist rhetoric about destroying Israel helped create a perception in Tel Aviv that delay was more dangerous than action. The result was pre-emptive war—driven as much by language as by troop movements.

More recently, India–Pakistan crises show how nationalist insult and public threats force leaders into escalation to preserve credibility, even when neither side benefits strategically from war. Each verbal escalation reduces space for quiet diplomacy and increases the risk of miscalculation.

These cases illustrate a recurring pattern: humiliation rhetoric does not merely signal resolve—it creates commitment traps. Leaders become hostages to their own words. The political cost of restraint rises. Escalation becomes easier than compromise.

The logic behind this strategy is coercive. By flexing muscles verbally and signalling readiness for war, each side seeks to force the other into negotiations on unfavourable terms. Humiliation becomes a pressure tactic; mockery becomes psychological warfare. The aim is to enter talks from a position of perceived superiority.

But the result is never guaranteed. Escalatory rhetoric can overshoot its purpose. Instead of producing submission, it can harden resolve. Instead of facilitating negotiation, it can push both sides toward extreme positions from which retreat appears humiliating—or impossible.

As Thomas Schelling warned, when public commitments are fused with emotion and reputation, leaders lose control over escalation. In this sense, sarcasm and humiliation are not harmless preludes to diplomacy. They are dangerous instruments of brinkmanship—capable of extracting concessions, or igniting wars that neither side initially intended to fight.