Apocalypse and Hegemony: Competing Visions of the Middle East

How do the three Abrahamic religions view the Middle East through their religious lens?

In recent years, much has been said about the emergence of a “New Middle East.” Global powers, regional actors, and religious movements each project competing visions of what this “new order” should look like. Yet most of these blueprints are imposed from above—by authoritarian regimes, colonial legacies, or religious elites—while the voices of the people of the region remain sidelined.

To understand the struggle over the Middle East’s future, one must look beyond politics and into the deeper layers of history, religion, and imagination. The region has long been shaped by competing cosmopolitan traditions, colonial projects, and eschatological visions that continue to inform the present.

The Middle East as a Cosmopolitan Crossroads

For much of its history, the Middle East was less a fragmented battlefield and more a mosaic of coexistence. Empires rose and fell, but the region remained a cosmopolitan space where multiple cultures, religions, and languages interacted. From Baghdad’s House of Wisdom to multi semi-Andalusian convivencia cities orcos MENA, the region was a global hub of intellectual, commercial, and spiritual exchange.

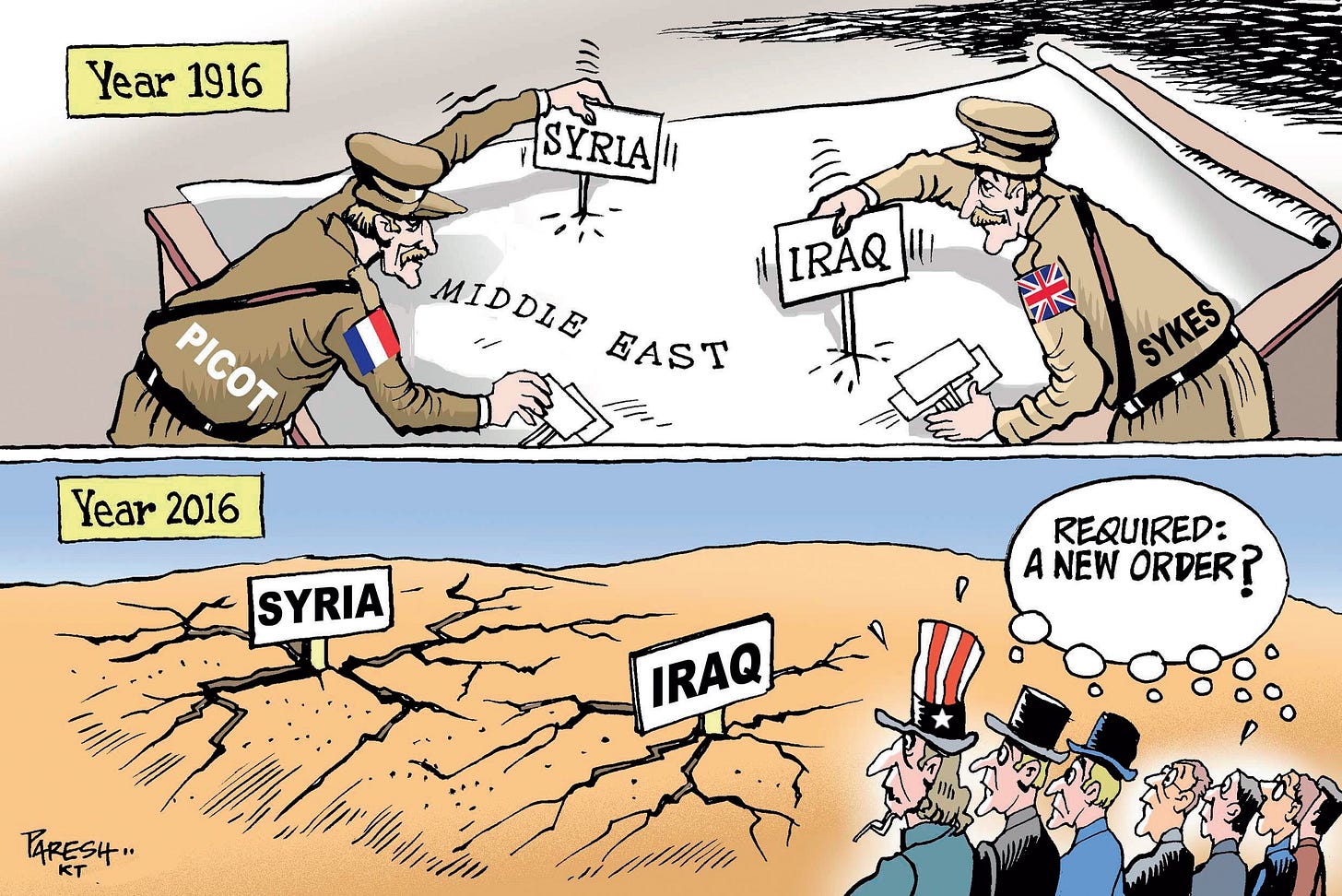

This pluralism was disrupted in the 20th century. After World War I and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Sykes-Picot Agreement and other colonial arrangements carved the region into artificial states with fragile borders. What followed was a century of instability, with national identities imposed from outside often clashing with older, pluralistic realities.

The “New Middle East” as a Colonial Project

Since the early 20th century, Western powers have consistently sought to reshape the Middle East according to their own hegemonic designs. The discourse of a “new” or “reformed” Middle East often masks a colonial logic.

And until today, from proposals to partition Iraq along sectarian lines, to ideas of annexing Lebanon to Syria, to the expansionist ambitions of Israel backed by U.S. policy, the rhetoric of “renewal” often comes at the expense of regional peoples. One of the most extreme recent examples was the Trump administration’s tacit support for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s suggestion that Palestinians could be displaced into neighboring Arab states—an echo of older colonial engineering.

The “new Middle East” promoted by global powers, then, is not new at all, but a continuation of colonial restructuring.

Jewish–Christian Eschatology and Political Power

Religious imagination has also played a central role in shaping visions of the region. Within Jewish and Christian traditions, despite sharp differences, there exists a shared belief in a Messiah who will return to establish justice.

For Christians, this figure is Jesus returning in the Second Coming; for Jews, it is a future Messiah yet to arrive. In both cases, some groups—especially in the modern era—have translated eschatology into political ideology.

In particular, some Jewish and Christian Zionists argue that preparing for the Messiah requires the Jewish return to the Holy Land and the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem—an act that would mean destroying al-Aqsa Mosque. This belief has fueled religious motivations behind unwavering U.S. and Western support for Israel, in tandem with economic and strategic considerations.

Thus, eschatology is not just about theology—it informs state policy, settler-colonial practices, and global alignments.

Islamic Eschatology: The Mahdi and the Return of Jesus

Islamic traditions offer their own eschatological framework. Both Sunni and Shiʿa Muslims believe in the coming of al-Mahdi, a messianic figure who will establish justice at the end of times, accompanied by the return of Jesus.

Here, however, the two traditions diverge. Sunnis typically see the Mahdi as a future figure yet to be born. Shiʿa, particularly the Twelvers, believe the Mahdi is the twelfth Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi, who was born in the 9th century and went into occultation, to reappear at the end of times.

Like in Christianity and Judaism, these beliefs carry political weight. They provide both a source of hope for oppressed communities and, at times, a justification for militant or political projects seeking to accelerate divine history.

Quietism vs. Activism in Eschatological Thought

Across all three monotheistic traditions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—eschatology divides into two broad orientations: quietism and activism.

• Quietist traditions hold that the coming of the Messiah is solely in God’s hands. Humanity has no role but to wait faithfully until the divine moment arrives.

• Activist traditions, often influenced by modern politics and colonial pressures, argue that believers must actively prepare the conditions for the Messiah’s return.

It is this activist reading that has driven both Christian Zionism in the U.S. and certain Shiʿa paramilitary movements in the Middle East. By contrast, quietist voices, though often marginalized in political discourse, emphasize restraint and humility before divine timing.

Between Apocalypse and Hope

The competing visions of a “new Middle East” are not merely geopolitical. They are rooted in religious imaginations of apocalypse and redemption. Yet what is often missing is the perspective of ordinary people in the region—those who must live under authoritarian regimes, foreign interventions, and religious projects imposed in their name.

If history teaches anything, it is that top-down projects built on domination rarely succeed in the long run. The Middle East’s true strength has always been its cosmopolitanism, its ability to hold together multiple identities, religions, and cultures. The challenge today is whether this heritage can be revived in the face of competing apocalyptic projects.

A truly “new” Middle East will not emerge from colonial designs or eschatological fantasies, but from the aspirations of its peoples for justice, dignity, and coexistence.